Adapted from Connecticut Case Studies, by Mark Williams

TEACHER'S SNAPSHOT

Course Topics/Big Ideas:

Democratic Principles and the Rule of Law, Role of Connecticut in U.S. History

Town:

Durham, Granby, Guilford, Lebanon, Litchfield, Lyme, Middletown, New Haven, New London, Norwich, Simsbury, Statewide, Stratford, Wethersfield, Windham, Windsor

Grade:

Grade 8, High School

Lesson Plan Notes

During the summer of 1787, fifty-five delegates from the original states met in Philadelphia to write a new constitution for the United States of America. What they were supposed to be doing was drafting amendments to the Articles of Confederation, but it did not take them long to realize that a major revamping was in order. While many students study the debates and compromises from the Philadelphia Convention and then look at The Federalist Papers as part of a discussion of ratification, fewer examine ratification at the state level. Through study of local debates over local concerns—taxation, priorities of agrarian vs. urban/merchant communities, disposal of the lands in the Western Reserve, and the role of religion and the Church—students can see that even in a state which ratified quickly (fifth to do so) and relatively “easily” (by a vote of 128–40 at the convention on January 9, 1788), there were serious issues at stake, ones that Connecticut citizens knew would impact the future of their state and their nation.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

SUPPORTING QUESTIONS

- What were the main issues in the debate over the ratification of the Constitution in Connecticut?

- Who gets to decide how a nation should be governed?

- What happens when people have different opinions?

- What is the value of civil discourse in a democratic society?

ACTIVITY

This activity should follow students’ study of the drafting of the Constitution in Philadelphia, looking at “what comes next” in the ratification process. Allow at least one class period for looking at the historic documents and newspapers and additional home and class time to prepare for and hold the mock convention.

Introduction and Document Analysis

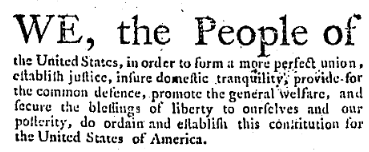

Introduce the compelling and supporting questions that will guide the inquiry and have students generate any questions about the ratification process that they might already have based on their earlier study. If they need to refer to the Constitution itself at any point during the inquiry, a PDF version of the document, as published in the Connecticut Courant on October 1, 1787, is provided in the toolkit.

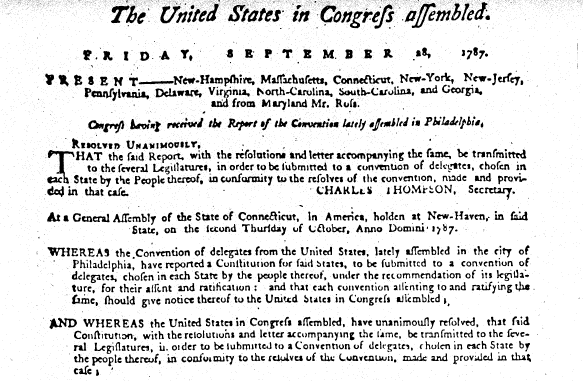

Start with a brief look at the “Call for a Convention” and short article from the October 8, 1787 Connecticut Courant to discuss what the next step was after the Philadelphia Convention. (Note: students may need to be told or reminded that many 18th-century documents/newspapers used the “long s,” which looks like an “f,” at the beginning or in the middle of words in place of the familiar “s.”)

Next, give students time to examine the newspapers articles from November/December 1787. You may wish to distribute different articles to different students/pairs/small groups. Ask students to consider:

- Who was the author?

- Who was the intended audience?

- What information is being communicated?

- Is the author in favor of the new Constitution or against it?

- What arguments are being posed? What issues seem to be of greatest concern to the author?

Role-play

After consideration of the original documents, distribute the roles for the ratification debate. Make clear that these were not the ONLY delegates to the convention, just some of the men who attended. If you have more than 20 students in your class, you could ask someone to play Jedidiah Strong of Guilford, who was the Secretary and called the roll when it was time to vote. Another student could play Nathan Strong, the minister who gave the opening prayer. If you have fewer than 20 students, you can leave out some roles; however, you should try to maintain the roughly 3:1 pro-ratification to anti-ratification ratio.

While some of the role sheets include excerpts from actual speeches, each student should be encouraged to use the information provided, as well as ideas pulled from the Constitution itself or the newspaper articles already examined, to develop their short argument to present at the debate. Students may need to do some additional research into topics mentioned in their role sheets, such as commutation, the Western Reserve, the New Lights, etc., in order to develop a clearer argument for the debate.

Before the debate opens, students should be given time to “mingle” and discover which delegates might be their allies. Who else shares their concerns about taxation, how much power the central government should have, or the role of religion and the Church?

Matthew Griswold was elected president at the convention. This student should announce a few ground rules, such as raising hands for recognition, having each speaker state “his” name and town before speaking, not interrupting unless recognized by the person who has the floor, etc. The convention of 1788 discussed the Constitution article by article. This is the best way to get students to look carefully at the specifics of the document, but there may not be time for you to do it this way.

Whatever the procedure, Griswold should first ask for a motion that the Constitution be ratified and then open the debate. When all views have been heard, or when time has run out, Griswold can entertain a motion that a vote be taken. A roll-call vote is the best technique, so students can see which delegates are voting which way. The delegates included in this activity are (in alphabetical order):

Capt. Ephraim Carpenter

Eliphalet Dyer

Pierpont Edwards

Oliver Ellsworth

Hezekiah Holcomb

Gen. Jedediah Huntington

Gov. Samuel Huntington

William Samuel Johnson

Richard Law

Amasa Learned

Stephen Mix Mitchell

William Noyes

Gen. Samuel H. Parsons

Col. Noah Phelps

Roger Sherman

Gen. James Wadsworth

Gen. Andrew Ward

William Williams

Oliver Wolcott

As a wrap-up, have students circle back to the compelling and supporting questions. What were the issues at hand, how were decisions made, and who was making the decisions in 1787/1788? Who was included in the conversation? Who was left out? What did the final decisions mean for a state like Connecticut?

OPPORTUNITIES FOR ASSESSMENT

- Students create a broadside/poster communicating their historical character’s perspective on the new Constitution, including a pro or con slogan and persuasive cartoons or statements.

- Following the debate, students take on the role of a newspaper reporter and write a short article covering the highlights of the convention.

- Students write a letter to the editor of the Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer from the perspective of someone NOT included in the ratification debate (perhaps a woman, a laborer, a person of color, or a person who is not a member of a Congregational Church congregation.) Is this person in favor of the Constitution, against it, or feel it will not make a difference in day-to-day life?

RESOURCE TOOL KIT

Call for a convention to ratify the Constitution, September 28, 1787.

“United States in Congress Assembled.” Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer, October 8, 1787, pg. 3.

United States Constitution. Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer, October 1, 1787.

Sherman, Roger; Ellsworth, Oliver. Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer, November 5, 1787, pg. 1.

“Hon. Mr. Gerry’s Objections to signing the National Constitution.” Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer, November 12, 1787, pg. 2.

“To the Landholders and Farmers…” Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer, November 26, 1787, pg. 1.

“Unconstitutionalism.” Middlesex Gazette, December 10, 1787.

Twenty roles for delegates at the state ratification convention, January 1788.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Places to GO

Connecticut’s Old State House, Hartford, CT

Site of the earlier State House, where the opening and closing ceremonies of the Convention were held.

Center Church: First Church of Christ in Hartford, Hartford, CT

Site of the earlier First Congregational Church (the third Meeting House in Hartford,) where the debates over ratification of the Constitution were held.

Oliver Ellsworth Homestead, Windsor, CT

Home of Connecticut delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and representative at the Ratification Convention in Hartford.

Things To DO

Websites to VISIT

Center for the Study of the American Constitution, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of History

Articles to READ

“Connecticut on the Eve of Ratification” by Mark Williams, 1989 (PDF)

ConnecticutHistory.org: