Tracey Wilson

Educational Consultant, West Hartford Town Historian, and Witness Stones Project Director

TEACHER'S SNAPSHOT

Themes:

Cultural Diversity and an American National Identity, Cultural Diversity and Connecticut State Identity, Economic Prosperity and Equity

Town:

Farmington, Hartford, West Hartford

Historical Background

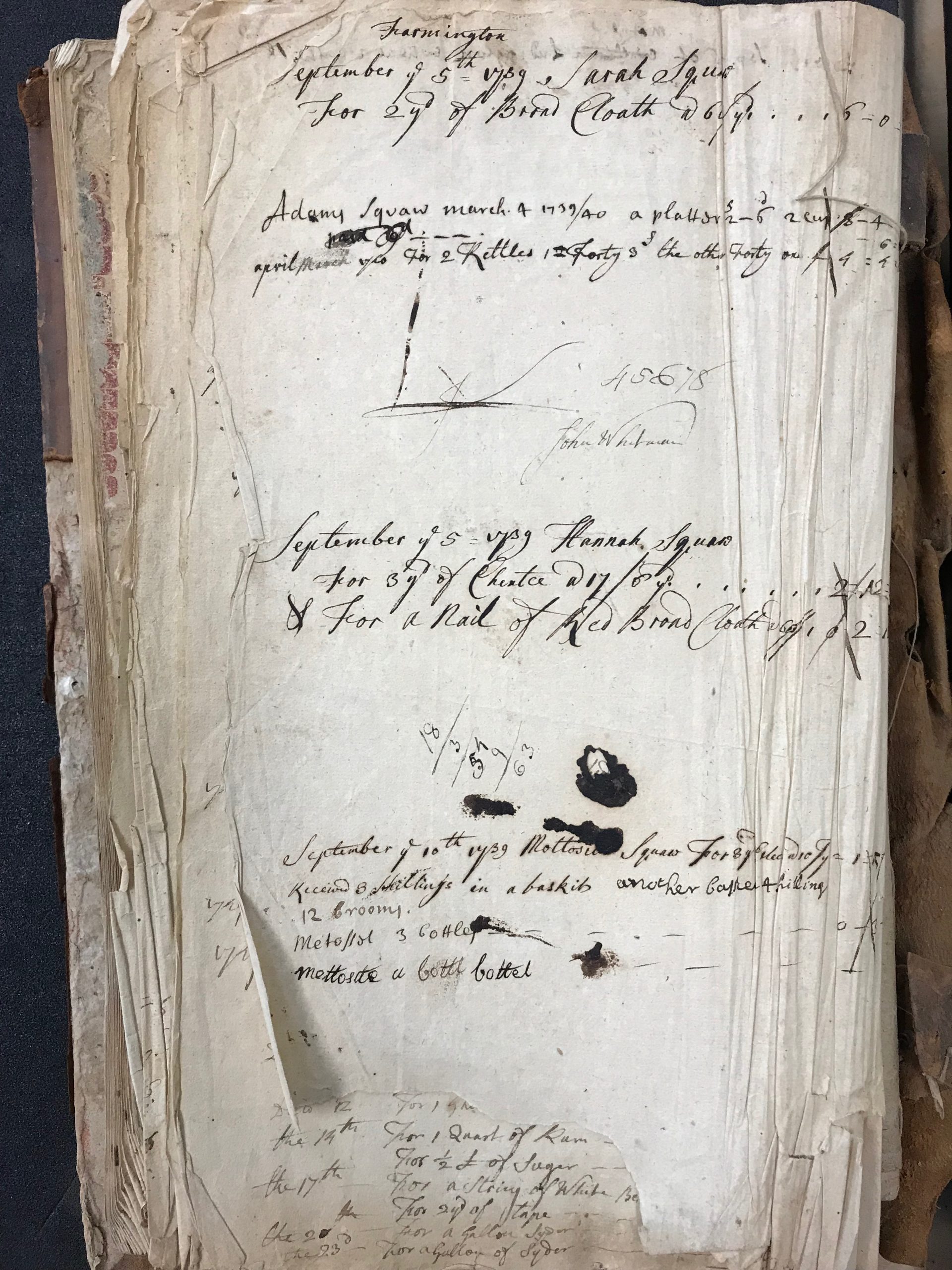

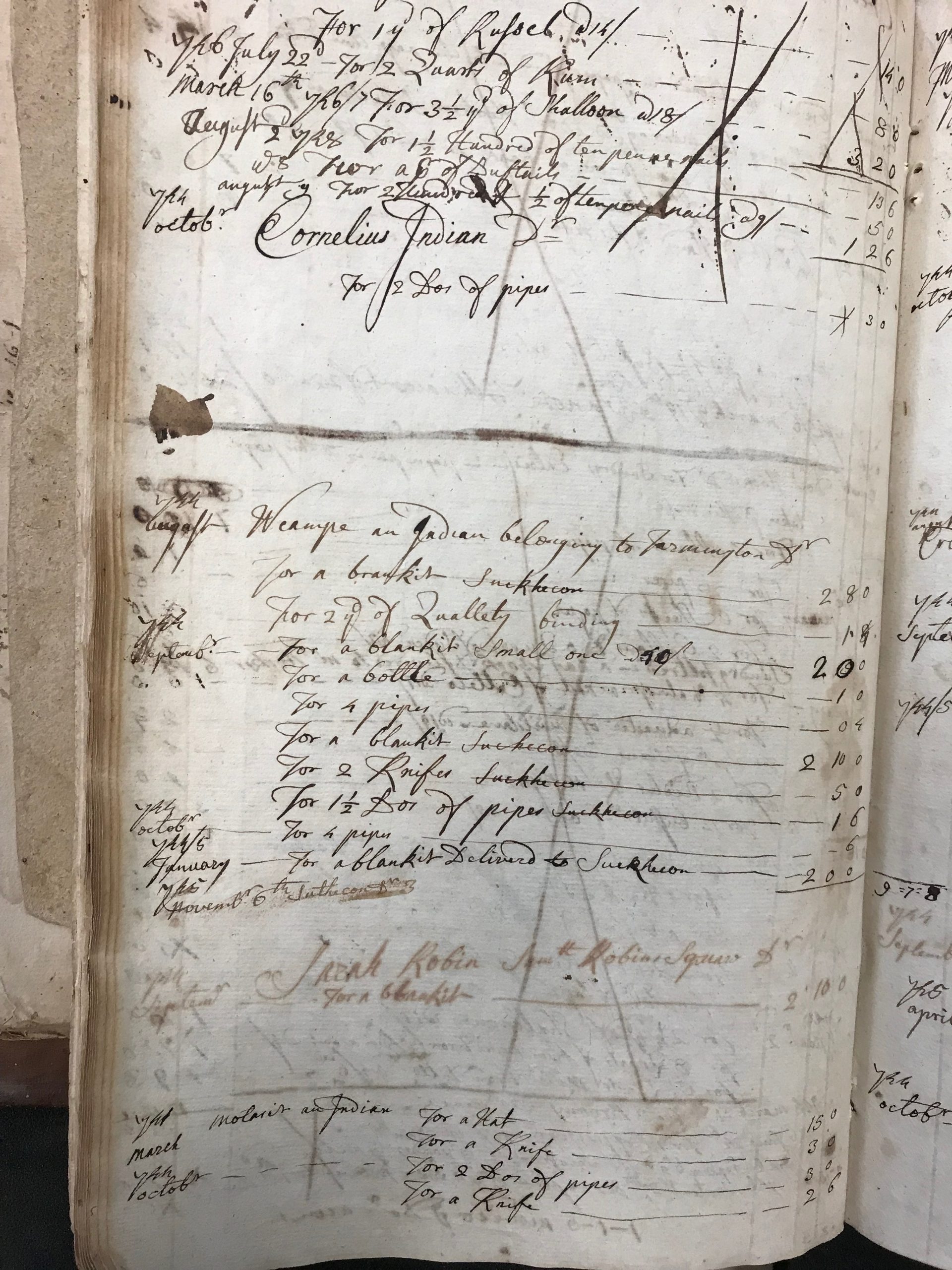

Until 1759, the Tunxis controlled a tract of land in Farmington and attracted Wangunk, Siacog, and Quinnipiac people to their settlement. The Tunxis lived as a largely agricultural community, farming corn, beans, and squash, as well as hunting and fishing in the Pequabuck and Farmington Rivers in an area called “Indian Neck” by the English. Some English and enslaved people from Africa also lived in the Tunxis community. Tunxis women were traders, clothing makers, healers, and political leaders. Some of these roles differed from those of English women. For a long time, historians mostly left Indigenous people out of written histories of the colonial period once the 17th century epidemics, Pequot War (1636-7), and King Philip’s War (1675-76) were over. We know from historical documents, though, that Tunxis women and men from Farmington traded with an English man named John Whitman from the West Division of Hartford (now West Hartford) in the mid-1700s. Tradesmen, craftsmen, doctors, and lawyers in the 18th and 19th centuries kept account books to record transactions with their customers. Between the 1730s and the time he died in 1800, John Whitman did business with residents of the West Division and beyond. He sold cloth, foodstuffs, hardware, spirits, and services and accepted in exchange (“contra”) cash, labor, livestock, and agricultural and manufactured products. In his account book, he recorded the date, what was purchased, and its value under each customer’s name. He also recorded the payment. Whitman traded with many people from Farmington, where his father Rev. Samuel Whitman was the minister of the Congregational Church. He had at least 14 Tunxis customers, 10 of whom were women. Whitman also traded with women of English descent, but it was rare and seemed to be limited to widows.

D1: Potential Compelling Question

D1: POTENTIAL SUPPORTING QUESTIONS

- What items did the Tunxis women and men trade to the English?

- What items did John Whitman trade to the Tunxis?

- What do the items traded tell about life in the 18th century for both the Tunxis and the English?

D2: TOOL KIT

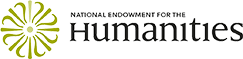

Map of the State of Connecticut Showing Indian Trails, Villages and Sachemdoms. Made by Hayden L. Griswold for the Connecticut Society of the Colonial Dames of America, 1930. University of Connecticut Library, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC).

Illustrated excerpts from John Whitman account book 1739-1746 (with transcriptions). Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Photographs by Tracey Wilson. PDF Version.

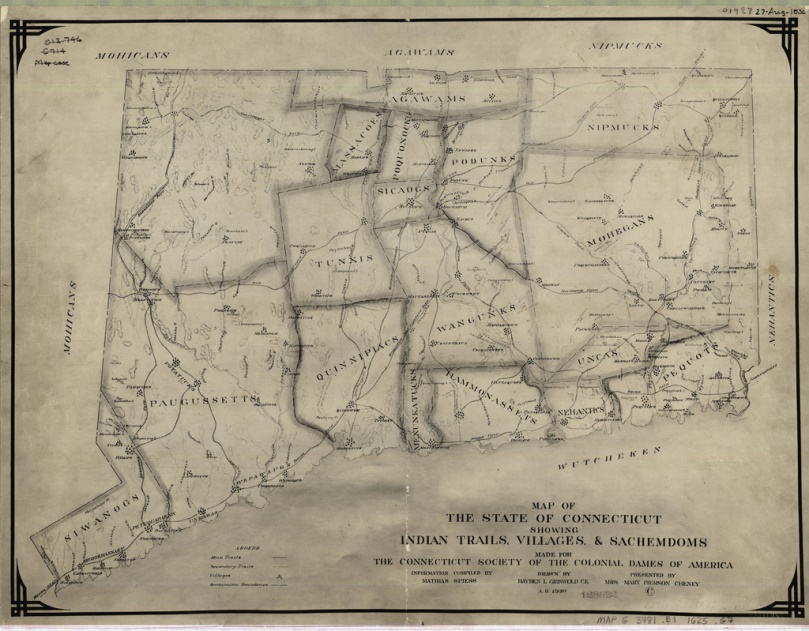

Excerpt 1 from John Whitman account book 1739-1746. Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Photograph by Tracey Wilson.

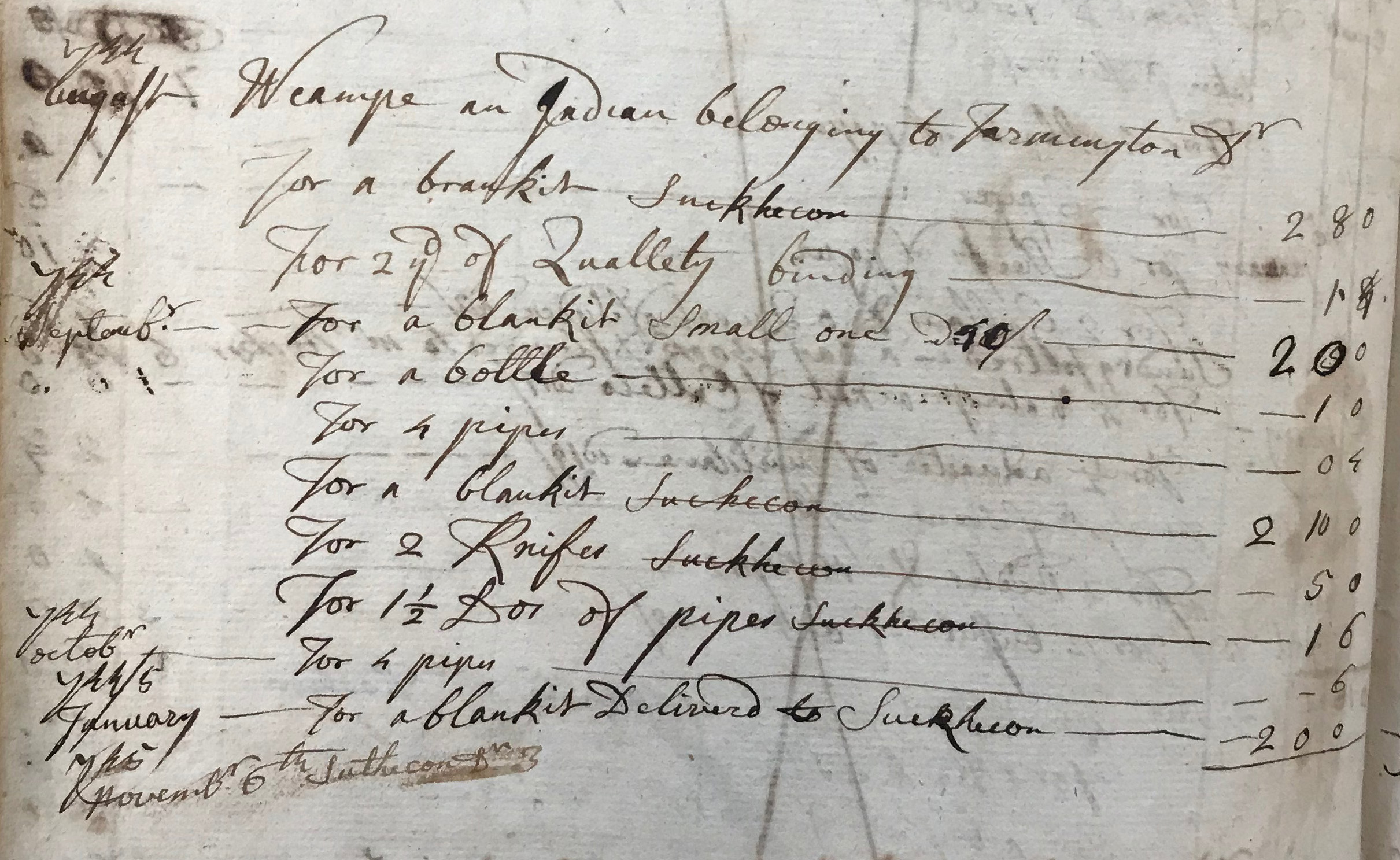

Excerpt 2 from John Whitman account book 1739-1746. Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Photograph by Tracey Wilson.

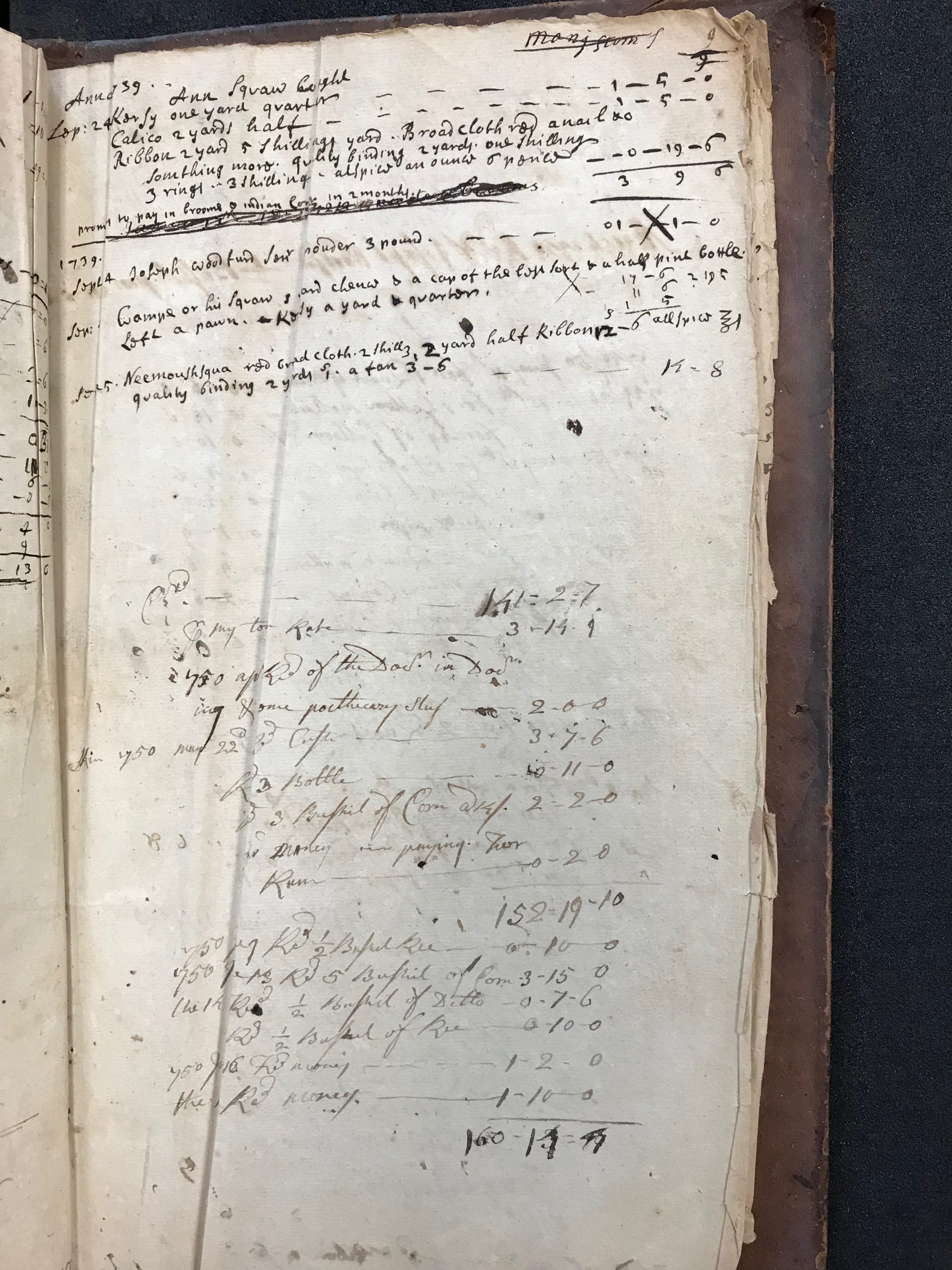

Excerpt 3 from John Whitman account book 1739-1746. Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Photograph by Tracey Wilson.

Excerpt 4 from John Whitman account book 1739-1746. Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Photograph by Tracey Wilson.

Transcription of excerpts from John Whitman account book 1739-1746. Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Transcribed by Tracey Wilson.

D3: INQUIRY ACTIVITY

1. Start by introducing the compelling and supporting questions and showing the 1930 map of “Indian Trails, Villages, and Sachendoms” to help orient students as to where, geographically, the Tunxis lived. Help students identify their own town/region on the map as well.

2. Share the information provided in the PDF about the English currency used at the time, and then examine together the annotated version of the first excerpt from John Whitman’s account book. Note that this document lists “Ann Squaw” as the customer at the top of the page. (This is a good opportunity to explain to students that “squaw,” although a term commonly used by English colonists to identify an Indigenous woman, is now considered to be racist, sexist, and derogatory. Its use here is important, however, as it indicates that much of Whitman’s business was with Indigenous women.) Analyze this page together. You can use the Library of Congress Primary Source Analysis worksheet as a starting point, asking students what they SEE, THINK, and WONDER about the document in front of them. The handwriting can be very difficult to decipher, so a transcription is provided.

3. Either together as a class or in small groups, have students examine the other pages from the account book, with the help of the transcriptions and illustrations. Students should consider: What kinds of items do the Tunxis buy from Whitman? What are the most expensive items? What are the least expensive? What do you think these items would be used for? What do the Tunxis trade to Whitman in exchange? What would those items be used for? Why do you think each group has different kinds of items to trade? What clues do these items give us about what life was like in the mid-1700s for both the Tunxis and the English? What do you THINK and what do you WONDER after looking at this document?

4. Revisit the compelling question to wrap up the discussion and consider where students could find more information to answer additional questions they have.

D4: COMMUNICATING CONCLUSIONS

- Students will research one of the medicinal items listed in the account book and the kinds of ailments that were common in the 1700s. They could identify and compare these healing treatments to medicines/treatments used for the same illness today.

- Students will research 18th-century English money used in the American colonies. What did it look like? What was it made out of? How was it made? What were the relative values? Students can then compare prices for pipes, blankets, cloth, rum, and knives to see what was most valuable. Here is a valuable resource from Colonial Williamsburg about determining value over time.

- Students will identify Connecticut places with “Tunxis” in their names (or that of another tribe that lived in their area). Students could research and create an exhibit or display about the Tunxis (or other group) and offer to share it with the proprietors.

- Students will visit the Tunxis monument in Farmington (or look at images of it) and create a proposal for how it could be updated.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Place to GO

Mashantucket Pequot Museum, Mashantucket

Institute for American Indian Studies, Washington

Things To DO

Visit the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History to see John Whitman’s account book in person (by appointment only).

Visit the Tunxis monument in Farmington and consider how it might be updated.

Websites to VISIT

Native Northeast Research Collaborative

Native American Research Subject Guide, Connecticut State Library

Articles to READ

“Breaking the Myth of the Unmanaged Landscape” by Tobias Glaza, with Paul Grant-Costa for Connecticut Explored. ConnecticutHistory.org.

“An Interdependent Colonial World” by Tracey Wilson. May 18, 2020.

“The Historic District of Farmington Village” by The Farmington Historic District Commission.

“This Week in New England Native Documentary History” by Paul Grant-Costa. Op-Ed: The Blog of the Yale Indian Papers Project. May 31, 2013.

“Interior Secretary Deb Haaland moves to ban the word ‘squaw’ from federal lands” by Bill Chappell. NPR. November 19, 2021.