Christine Gauvreau, Project Coordinator, Connecticut Digital Newspaper Project,

Connecticut State Library

TEACHER'S SNAPSHOT

Subjects:

Food, Immigrants, Patriotism, Politics & Government, Propaganda, Rights & Responsibilities of Citizens, Women, World War I

Course Topics/Big Ideas:

Role of Connecticut in U.S. History

Town:

Statewide

Grade:

High School

Lesson Plan Notes

By the time the United States entered WWI, farming in Europe had been devastated. U.S. allies were starving. Washington initiated a patriotic program to increase food production and to induce the people to voluntarily conserve food on the household level. Five billion dollars in food was delivered to Europe. As part of the effort to provide this food to the Allies, the federal government set out to get 22 million households to sign a food conservation pledge. Robert Scoville, head of the Connecticut Food Administration, and George M. Landers, chairman of the Connecticut Committee of Food Supply, organized the drive in this state. In November 1917, their goal for Connecticut was 200,000 signed pledge cards.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

SUPPORTING QUESTIONS

- What did the U.S. Food Administration and the Connecticut Committee on Food Supply hope to accomplish with the food pledge campaign?

- What methods were employed to achieve these goals, who employed these methods, and to whom did they appeal?

- How did gender, income level, religion, and place of national origin affect how residents experienced or evaluated the food pledge campaign?

- What opposition, if any, was there to home front mobilization campaigns?

ACTIVITY

- Introduce the compelling question and the initial supporting questions that will drive the inquiry.

- Together as a class, examine Source #1 (“Food will Win the War” poster.) Track students’ observations and questions about the source. What clues does the poster provide about the goals and methods of the U.S. Food Administration?

- Next, break the class into smaller work groups/pairs.

- Assign 1-3 primary sources from Part 2 of the toolkit to each group/pair. Allow the small groups time to develop responses to the initial supporting questions based on the primary sources and generate additional supporting questions.

- Ask each work group to briefly share their source(s), findings, and questions with the rest of the group.

- Discuss responses to the compelling question based on the evidence from the primary sources provided.

- Have the class (as a whole) propose avenues for further research that interest them, explaining why they think such research might be important.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR ASSESSMENT

- Students will write a response to either the original compelling question or another student-generated question, citing the primary sources they relied upon. Students will include thoughts about what kind of further research would be needed if they were to pursue the question further. Students will then gather with their work groups, share their answers, and gently critique each others’ work, choosing one response to share with the class as a whole, if desired.

- Imagining themselves as a Connecticut resident in 1917, students will write a letter to the editor of their local newspaper in response to the question: “Should the names of those families who do not sign the Food Pledge be published in our newspaper?” Students may select or be assigned different perspectives from which to respond, such as a struggling immigrant housewife, the mother of a soldier fighting in France, a local pacifist, etc.

- Students will investigate the dietary/food conservation recommendations made by the United States Food Administration and Connecticut Committee of Food Supply. What kinds of foods/meals were recommended to help with the war effort? What would nutritionists/dietary specialists think of these recommendations today? To get started, students could look at these resources:

- Cutting the meat bills with milk.

- Wheatless recipes tested in the experimental kitchen of the Food administration, 1918.

- Save the products of the land–Eat more fish-they feed themselves.

- War time cookery: a collection of recipes that will not only reduce the high cost of living but are especially adapted to wheatless and meatless days, 1917.

- Economical war-time cook book, ca. 1918.

- Eat more corn, oats and rye products – … Eat less wheat, meat, …

- Wholesome – nutritious foods from corn.

- War economy in food, with suggestions and recipes for substitutions in the planning of meals, 1918.

- Sugar–save it.

RESOURCE TOOL KIT

Things you will need to teach this lesson:

Part 1

“Food will win the war. You came here seeking Freedom. You must now help to preserve it. WHEAT is needed for the allies.” United States Food Administration, ca. 1917. National Archives.

Part 2

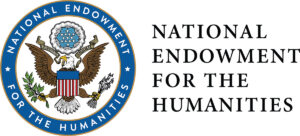

“‘Eat Plenty, Wisely, Without Waste,’ Says Hoover: Work of the Food Administration Under Herbert C. Hoover—A War Emergency Measure—America’s Food Problems—Woman’s Part.” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, October 17, 1917, 12:1-7. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

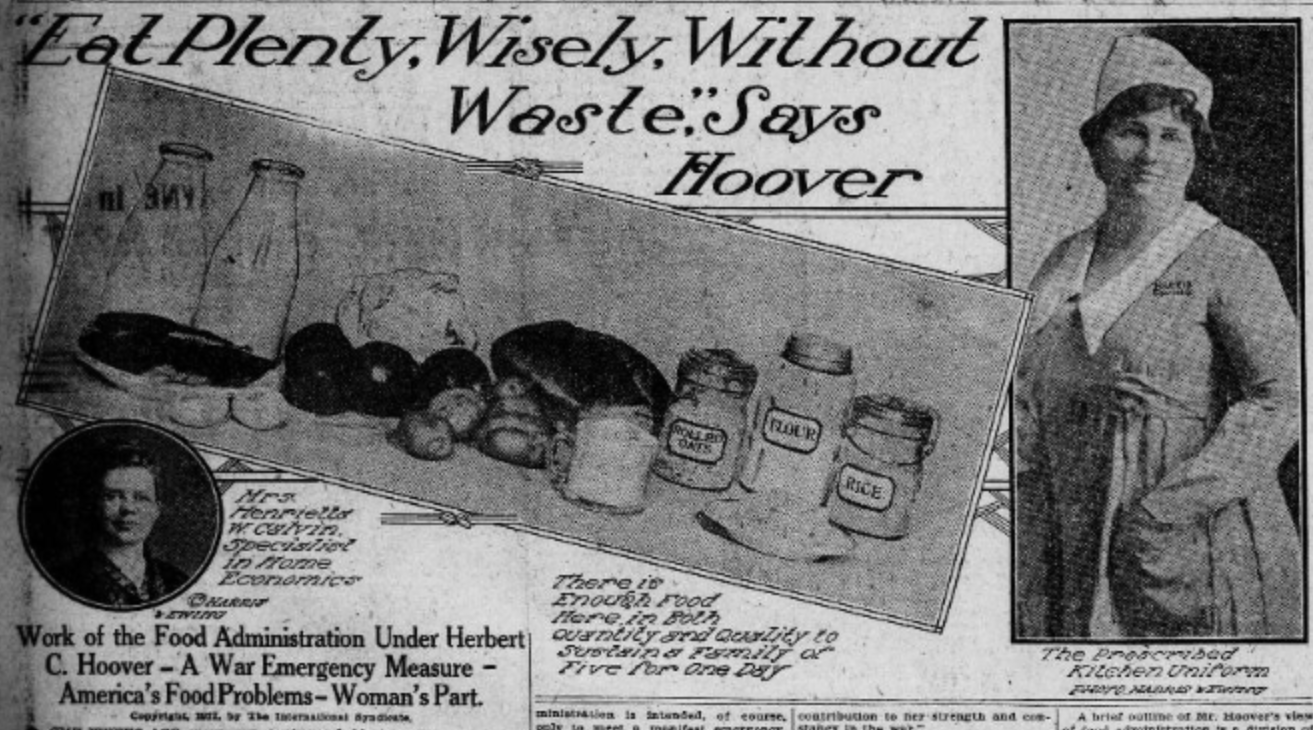

“Women of Connecticut: Are You Helping?” Poster from the Committee of Food Supply, Connecticut State Council of Defense, 1917-1918. Connecticut Museum of Culture and History.

U.S. Food Administration Window Card. Fairfield Museum and History Center.

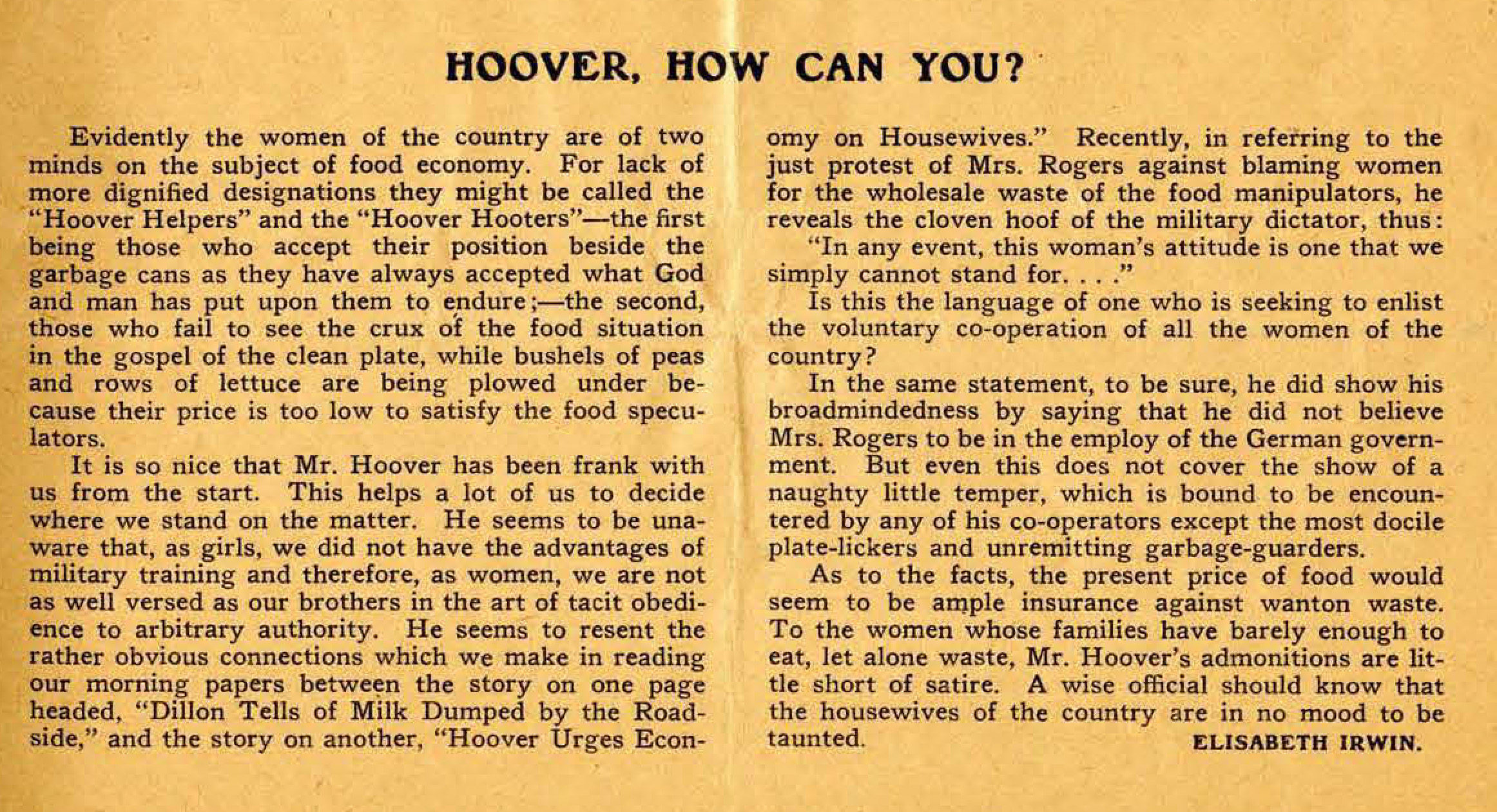

“Hoover, How Can You?” Four Lights: An Adventure in Internationalism, July 14, 1917, p. 2. Published by the Women’s Peace Party, New York. Swarthmore College.

“State Food Conservation Committee Save Quantity Food Through Girls Army.” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, December 20, 1917, 9:1-2. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

“Thousands Working in Campaign: Canvassers Explaining Food Pledge Movement to Housewives Throughout the Country—Those Who Refuse to Sign Are Pro-German—Norwich Expected to Net 4,500 Pledges.” Norwich Bulletin, November 3, 1917, 3: 3-4. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

“German Agents Hindering Food Savings Plans.” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, October 31, 1917, 1:1-2. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

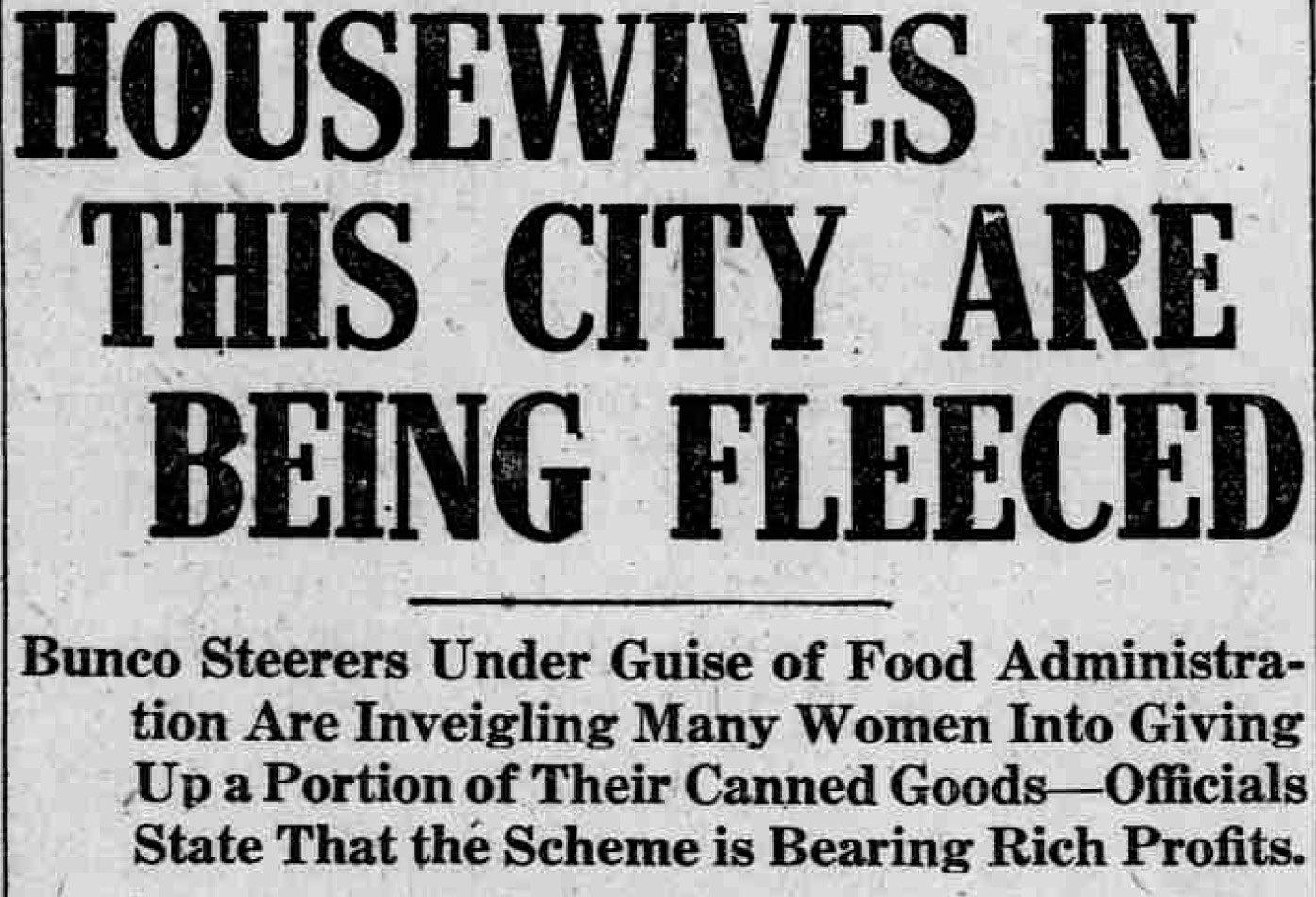

“Housewives in This City Are Being Fleeced.” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, November 1, 1917, 1:3-4. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

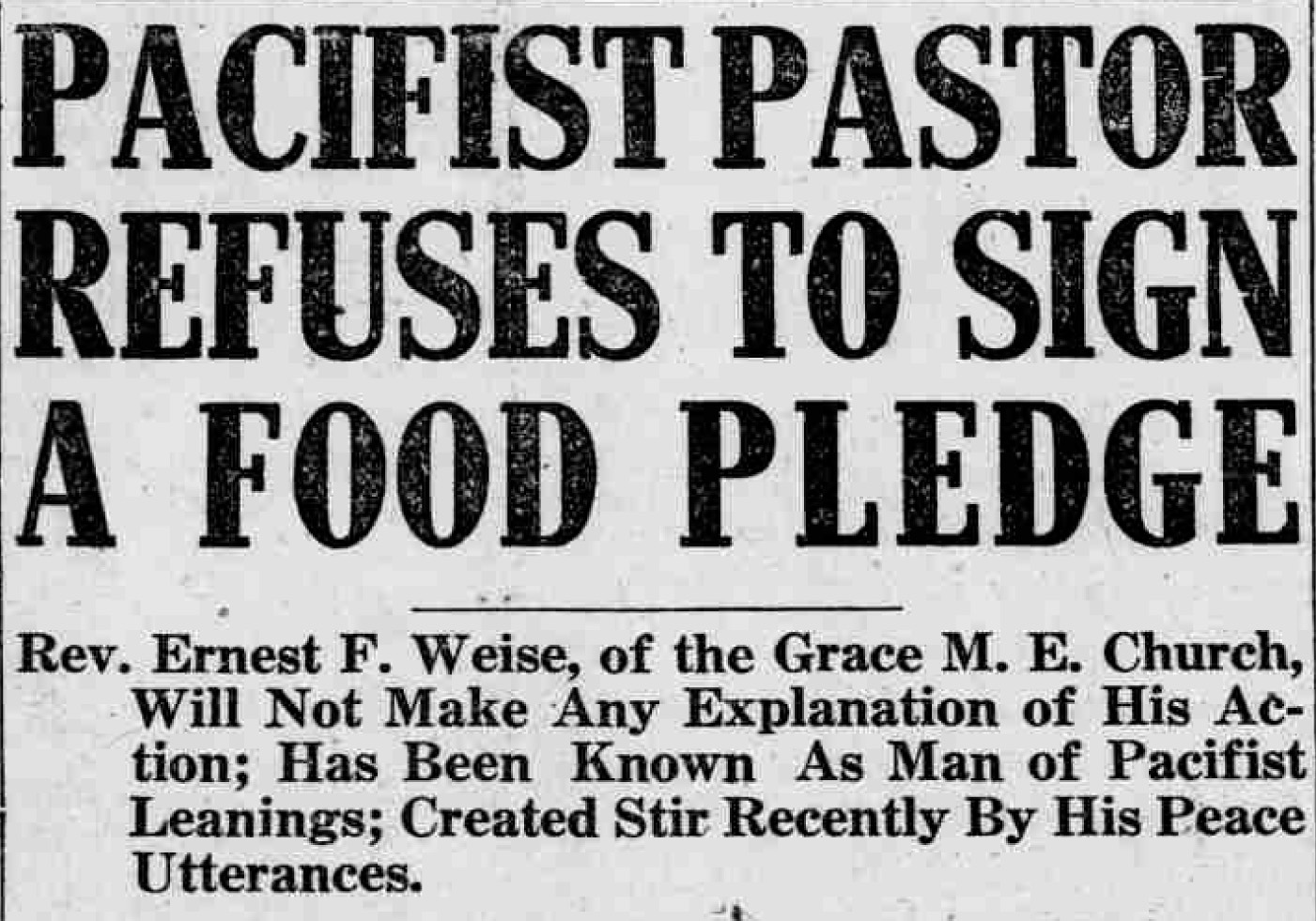

“Pacifist Pastor Refuses to Sign a Food Pledge.” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, November 2, 1917, 1:4-5. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

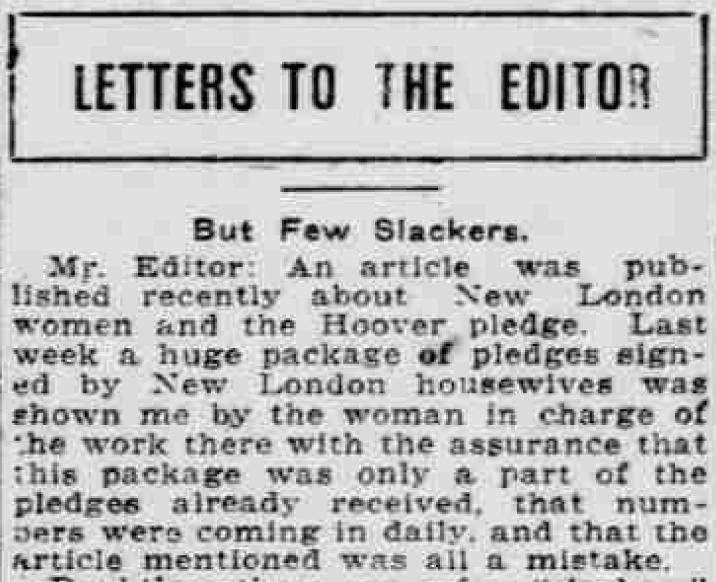

“Letters to the Editor: But Few Slackers.” Norwich Bulletin, August 11, 1917, 4:6. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Places to GO

Interested to know more about what went on in your town during World War I? Visit your local library and ask if they have newspapers from the time on microfilm or in bound volumes.

Visit your local historical society to discover what original materials they have from WWI. You may find posters, photographs, letters, or personal accounts.

Things To DO

Search Connecticut newspapers in Chronicling America to learn more about food riots taking place in both the United States and Europe during World War I. Using the Advanced Search, limit your search to 1914-1918 and the phrase “food riots.” How do these riots and the responses to them compare to contemporary events globally? Is food still a subject of social unrest? What other issues cause demonstrations or uprisings?

Search Chronicling America to explore how retail commerce was affected by the home front mobilizations in Connecticut. For example, on this newspaper page is an advertisement for a stove guaranteed to minimize “food shrinkage.” Do you think that they sold many units? How did other retailers appeal to the home front? Compile a portfolio of ads that used patriotism to sell their wares. Is this approach used today?

Websites to VISIT

Connecticut Digital Archive: Remembering World War One

International Encyclopedia of the Great War: Home Front

Articles to READ

ConnecticutHistory.org:

- “Food Needed to Win the War Comes from Washington.” This article was originally researched and written by Karen A. Stansbury for the Gunn Memorial Museum in Washington, Connecticut, for their exhibit, “Over There: Washington and the Great War.”

- “A New Source of Farm Labor Crops Up in Wartime.” by Gregg Mangan.

CTExplored.org: “Greenwich Women Face the Great War.” by Kathleen Eagen Johnson. Connecticut Explored, Winter 2014/2015.

Allen, John. “The Food Administration of Herbert Hoover and American Voluntarism in the First World War.” Germina Veris, 1/1 (2014).

Barr, Eleanor. “Part 1: Women’s Peace Party.” Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Collection (DG043). Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA.

Edelstein, Sally. “Women and Food Will Win the War—WWI.” March 14, 2016, Envisioning the American Dream.

Four Lights: An Adventure in Internationalism. Women’s Peace Party of New York City, January 27, 1917-June 12, 1919. Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Collection (DG043), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA.

Grayzel, Susan R. “Women’s Mobilization for War.” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014.

Kazin, Michael. “The War—Or American Promise: One Must Choose.” War Against War: The American Fight for Peace, 1914-1918. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Kennedy, David M. “The War for the American Mind” and “The Political Economy of War: The Home Front” Over Here: The First World War and American Society. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980, pp. 45-143.