by Rebecca Furer for Teach It

TEACHER'S SNAPSHOT

Subjects:

Business & Industry, Invention & Technology, Patriotism, Women, Work, World War I

Course Topics/Big Ideas:

Role of Connecticut in U.S. History

Grade:

High School

Lesson Plan Notes

World War I was the first conflict to see large-scale use of chemical weapons. Poison gases, such as chlorine, phosgene, and mustard gas caused blisters on the skin, blindness, lung damage, asphyxiation, and other injuries. The earliest German gas attack (at Ypres, France, in 1915) took the Allied forces by surprise, and soon afterwards the British and French started developing their own chemical weapons and protective gas masks. The United States ramped up its gas mask production in 1917–1918. The Red Cross spearheaded a campaign to collect fruit pits and nut shells for making gas mask filters. Several factories in Connecticut converted to gas mask production in order to meet the army’s needs. Hundreds of women in the state were recruited for this work.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

SUPPORTING QUESTIONS

- To what extent were women essential to the workforce during World War I?

- How did the U.S. government and the Red Cross mobilize people to participate in the war effort?

- In what ways did Connecticut industry influence World War I?

- How did Connecticut’s existing industrial infrastructure and workforce adapt to serve the war effort?

ACTIVITY

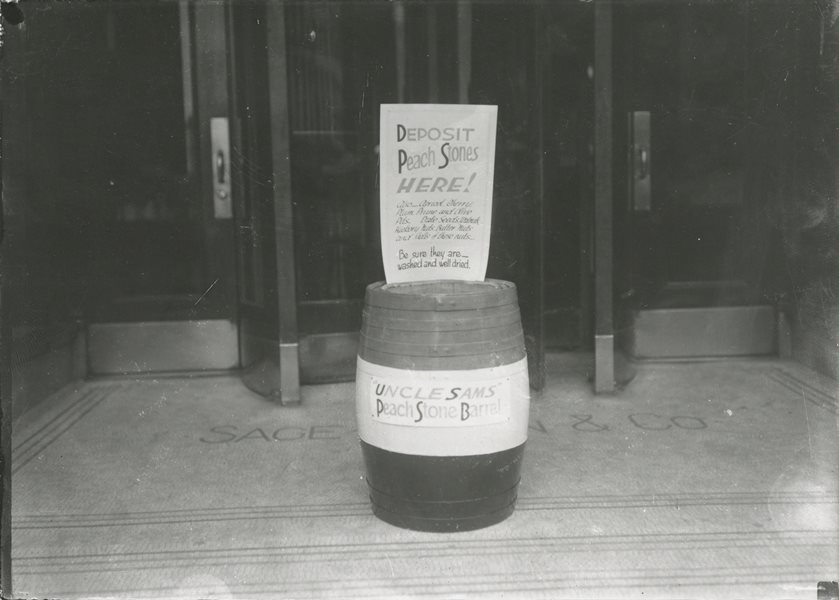

- Start by displaying the “Peach pit hogshead” image, preferably full screen, without the title/caption.

- Ask students to look closely at the image and share what they see. Encourage them to back up their comments with specific visual evidence. Ask, “What do you see that makes you say that?” You may want to use the Library of Congress Analyzing Photographs & Prints process (download Teacher’s Guide) to guide students’ looking. Assemble a list of questions that arise from the students’ examination of the photograph.

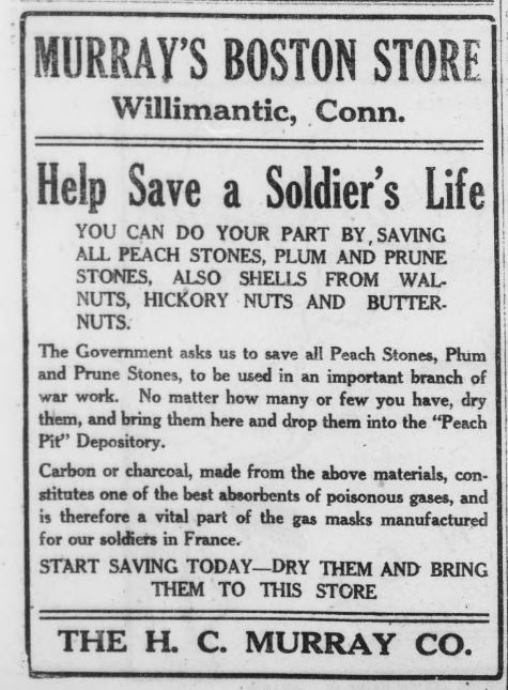

- Next, display or distribute the advertisement for Murray’s Boston Store in Willimantic. Once students have had a chance to read the advertisement, make a list of the new pieces of information students have gathered. See which questions from the initial list have now been answered, and make a list of additional/new questions.

- Select one, two, or all three of the short newspaper articles to share with students. You may wish to assign different articles to different students or have everyone read all of the articles. Ask students to:

OBSERVE: What information can they gather from the articles?

REFLECT: What do they think based on what they have read?

QUESTION: What does this article make them wonder? - You may want to use the Library of Congress Primary Source Analysis worksheet to help students organize and record their thoughts.

- Look back at the students’ list of questions for inquiry and/or at the suggested supporting questions. Discuss to what extent these primary sources help uncover answers to those questions or to the larger compelling question. Discuss additional questions the students have and sources or avenues for further inquiry.

NOTE: To see original film footage of gas mask production in 1918—from the peach pits to the final product—don’t miss this great source from the National Archives. Click on the hyperlink below and then on the film icon to start the video.

Silent video: Manufacture of Gas Masks, 1918, silent video (6:21). National Archives.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR ASSESSMENT

- Drawing on their examination of the primary sources in this activity and other related sources (see below for some suggestions), students will design a World War I-style poster promoting the collection of fruit pits for the war effort OR encouraging women to take on war work in Connecticut factories. Need inspiration? Check out the Library of Congress’s collection of World War I Posters.

- Students will research other Connecticut industries during World War I and compare them to the production of gas masks at the time. Who was employed? Where were the factories located? How did the products contribute to the war effort? Did the factories make something different before the war?

- Students will draft a letter to a state legislator or to the editor of their local newspaper advocating why—based on the study of history and the examination of primary sources—there should be a monument that recognizes the war efforts of Connecticut residents on the home front during World War I.

RESOURCE TOOL KIT

Things you will need to teach this lesson:

Peach pit hogshead outside Sage Allen & Company department store, Hartford, Connecticut ca. 1917-1919. Connecticut State Library, Dudley Photograph Collection.

Murray’s Boston Store (Willimantic) advertisement. Norwich Bulletin, Norwich, Connecticut, September 9, 1918. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

“Straw Hats Must Yield to Gas Masks: United States Rubber Buys Old Straw Hat Works at Milford.” The Hartford Courant, July 8, 1917, pg. 5.

“Local Plant Needs Women to Work on Gas Mask Rush Order.” The Hartford Courant, June 28, 1918, pg. 9.

“Women Answer Call For Gas Mask Work. More than 300 sign up at Hartford Rubber Works.” The Hartford Courant, June 30, 1918, pg. 6.

Library of Congress Primary Source Analysis Tool Worksheet

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Places to GO

Museum of Connecticut History, Hartford

Connecticut Museum of Culture and History, Hartford

Visit your local historical society or library to discover what original materials they have from WWI. You may find posters, photographs, letters, or personal accounts.

Things To DO

Take a look at some other primary sources related to this topic:

- Article: “Peach Stones Used for Gas Masks for Army.” The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer. (Bridgeport, Connecticut), September 26, 1918. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- Article: “Poison in Warfare.” The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer. (Bridgeport, Connecticut), February 21, 1918. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- Photograph: U.S. Marines standing in ranks with gas masks attached, France, 1918. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

- Photograph: Peach Pit tableau in Boston, ca. 1917-1918. National Archives.

- Silent video: Manufacture of Gas Masks, 1918, (6:21). National Archives.

Read a Book: Brown, Carrie. Rosie’s Mom: Forgotten Women Workers of the First World War. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 2002.

Websites to VISIT

Connecticut State Library: Connecticut in World War I

Remembering World War I, Connecticut Digital Archive

National World War I Museum and Memorial

Library of Congress: Guide to WWI Materials

Library of Congress: World War I

Articles to READ

ConnecticutHistory.org: World War I – Topic Page

CTExplored.org:

- “Greenwich Women Face the Great War: Our Contributions from the Home Front” by Kathleen Eagen Johnson, Connecticut Explored, Winter 2014/2015.

- “Women in the Workplace: From Steno Pool to Factory Floor” by Tracey Wilson, Connecticut Explored, Winter 2013/14.

“What America Looked Like: Collecting Peach Pits for WWI Gas Masks” by Brian Resnick, The Atlantic, February 1, 2012.

“Teaching History with 100 Objects: A Gas Mask for a Horse.” The British Museum.

Faith, Thomas I. “Gas Warfare.” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014.