by Rebecca Furer for Teach It

TEACHER'S SNAPSHOT

Subjects:

Military Service, Music, Patriotism, Propaganda, World War I

Course Topics/Big Ideas:

Role of the United States in World Affairs

Town:

Statewide

Grade:

High School

Lesson Plan Notes

After more than two years of neutrality, the United States formally entered World War I on April 6, 1917. At the time, the federal army and National Guard only numbered about 300,000 together. Enlistment quotas were established and volunteers were recruited, but to build up the military force, Congress passed the Selective Service Act on May 18, 1917. Registration for the draft began on June 5, 1917, and the first draftees were selected by lottery on July 20. Through July, men of draft age were still able to enlist voluntarily, if their draft number had not yet been called. Of the 4.8 million Americans who eventually served in the war, approximately 2 million enlisted as volunteers; 2.8 million were drafted.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

SUPPORTING QUESTIONS

- What official and unofficial tools were used to encourage/pressure men into voluntary military service in 1917?

- What messages did men receive in 1917 about participating voluntarily in military service—or not?

- In what ways were families of soldiers encouraged to show public support for sons or husbands in the service?

ACTIVITY

- Discuss the compelling and supporting questions that will guide the inquiry and add any additional student-generated questions to the list.

- Divide the class into five working groups, each with one primary source set from the toolkit.

- Start the observation and analysis process by asking students to identify what type of sources they have in their set: Photograph? Poster? Newspaper article? Advertisement? Sheet music? Artifact? Something else?

- Next, students will make a list of observations for each of their sources, indicating what they know by looking at or reading the source. Find helpful guiding questions for analyzing all different types of primary sources on the Library of Congress’s “Teacher Guides and Analysis Tools” page.

- After making detailed observations, students will move on to reflecting and posing hypotheses and ideas based on the clues available to them in the source. These may include who the intended audience was, what the purpose of the item was, what the historical context might have been, or whether such an item would be produced today—and why or why not.

- Finally, students will generate additional questions they have about their sources and ideas for where or how they could find out more.

- Each group will share the primary sources in their set with the class and together the students will revisit the compelling and supporting questions and discuss additional questions for inquiry.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR ASSESSMENT

- Students will create a word cloud representing the most common key words or phrases used in the primary sources examined by the class (e.g. man, flag, service, America, enlist, pride, etc.) To find free online tools to help with this activity, search for “free word cloud generator.”

- Students will examine the official recruitment website for one branch of the U.S. Armed Forces and identify the main messages communicated through the site. Students will then create a written piece or graphic organizer comparing this communication tool with one or more of the World War I primary sources examined in the inquiry activity.

- Students will investigate the Blue Star Families organization and write a letter or make a short video addressed to a local museum or theater informing them about Blue Star Museums or Blue Star Theatres. Students may choose to make a persuasive argument for why the museum or theater should participate in the program (make sure to check that they are not already involved!)

RESOURCE TOOL KIT

Things you will need to teach this lesson:

Document Set 1

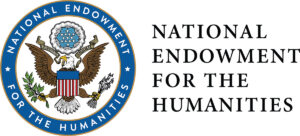

An enlistment banner hangs across Hartford’s Main Street, just before Pearl Street, urging men to enlist in the Connecticut National Guard or the regular army. Connecticut State Library, Dudley Photograph Collection.

A broadside or poster “Enlist now!” which calls for the enlistment of 64 men from Tolland County, Connecticut. Connecticut Museum of Culture and History.

Document Set 2

Poster “The Navy Needs You! Don’t Read American History – Make It!,” by James Montgomery Flagg for the U.S. Navy Recruiting Station, 1917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

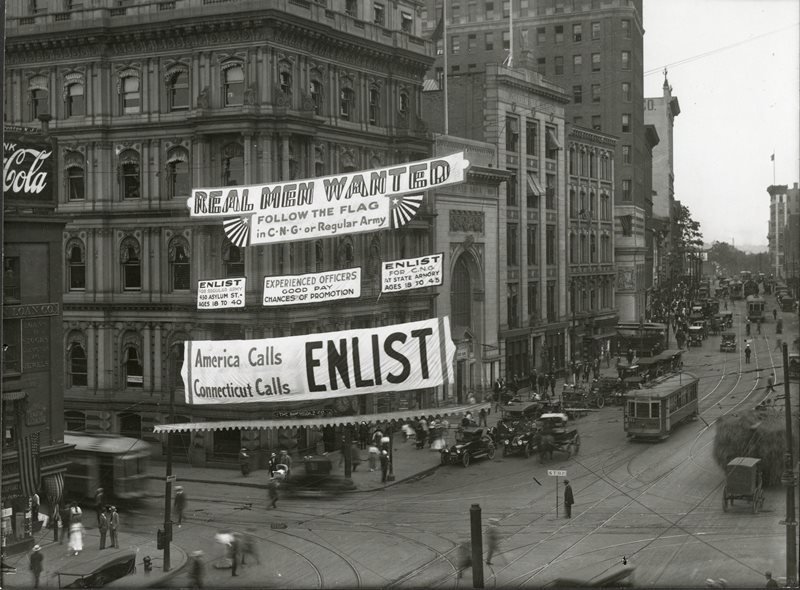

Poster “I Want You For The Navy: Promotion For Any One Enlisting, Apply Any Recruiting Station Or Postmaster,” by Howard Chandler Christy, 1917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

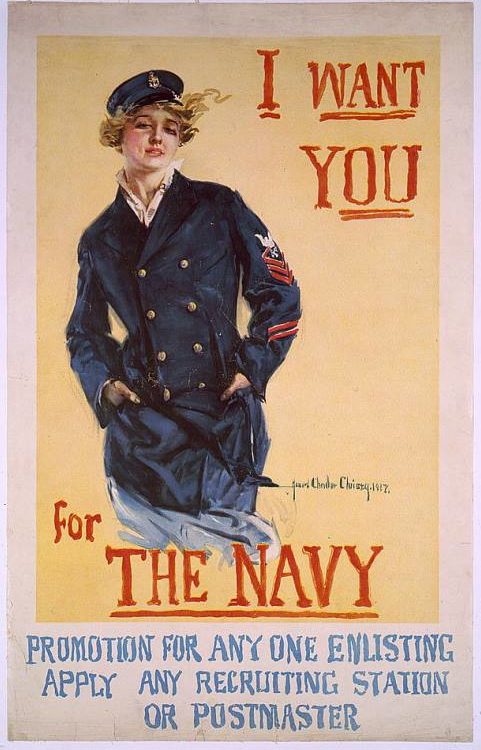

Poster “First Call: I Need You in the Navy this Minute! Our Country will always be proudest of those who answered the FIRST CALL,” by James Montgomery Flagg, ca. 1917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Document Set 3

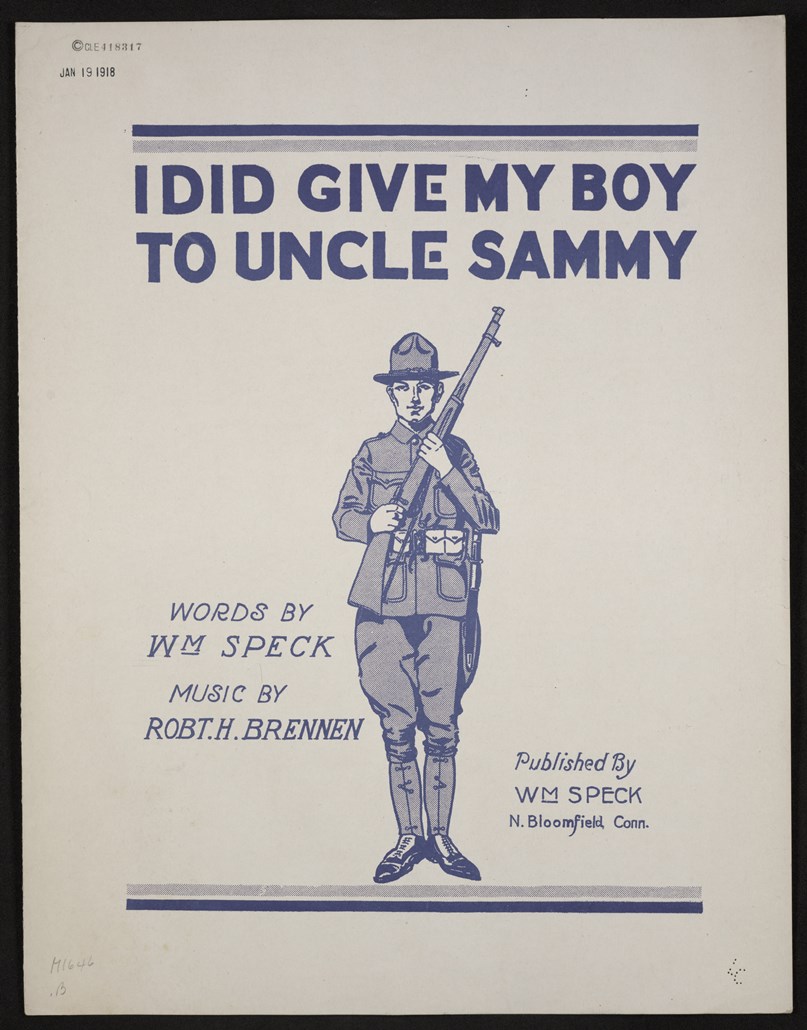

Sheet music “I Did Give My Boy To Uncle Sammy,” published in Bloomfield, CT, by Robert H. Brennen and W. Speck, ca. 1917. Library of Congress, Music Division, World War I Sheet Music Collection.

Sheet music “My Son, Your Country is Calling,” by Milton Charles Bennett, Hartford, CT, 1917. Library of Congress, Music Division, World War I Sheet Music Collection.

Document Set 4

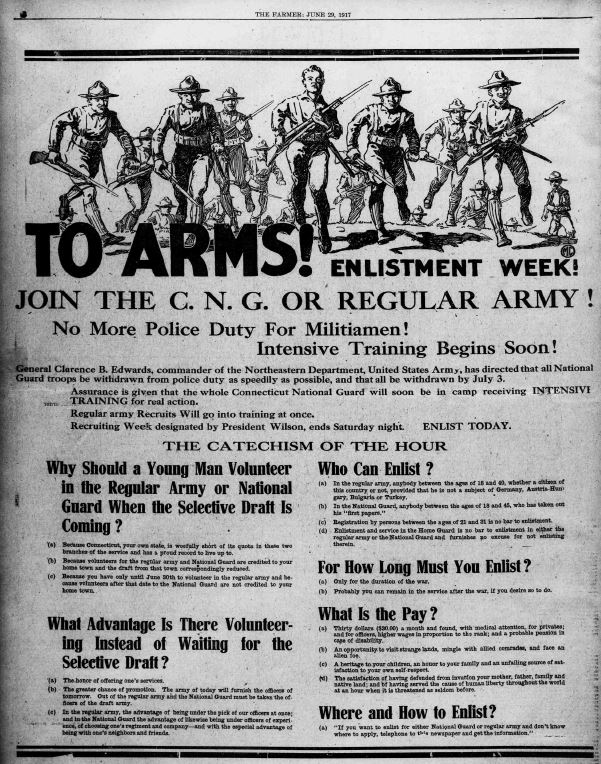

“To Arms!” a full page advertisement in The Bridgeport Evening Farmer, Bridgeport, CT, June 29, 1917. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

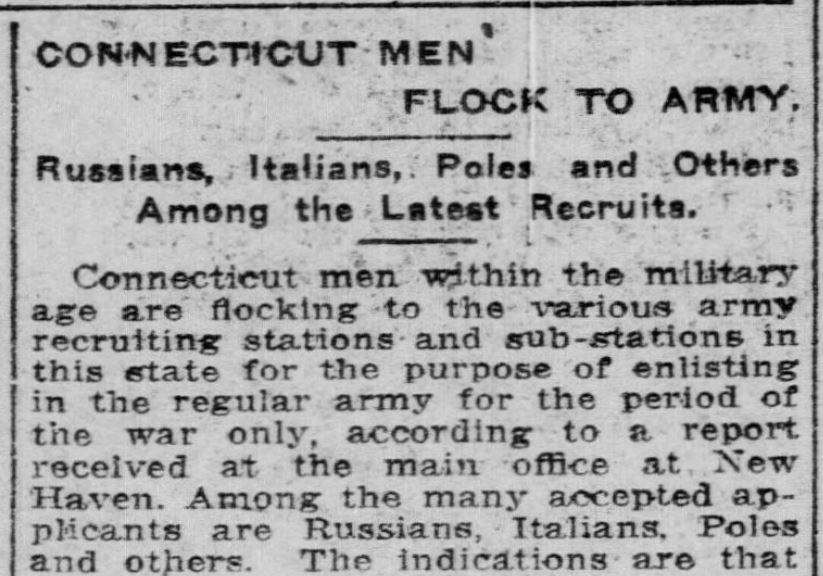

“Connecticut Men Flock to Army.” Norwich Bulletin, Norwich, CT, June 5, 1917. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Document Set 5

Handmade Service Flag, 1917. Connecticut State Library, 1850-2016, Department of War Records, Remembering World War One.

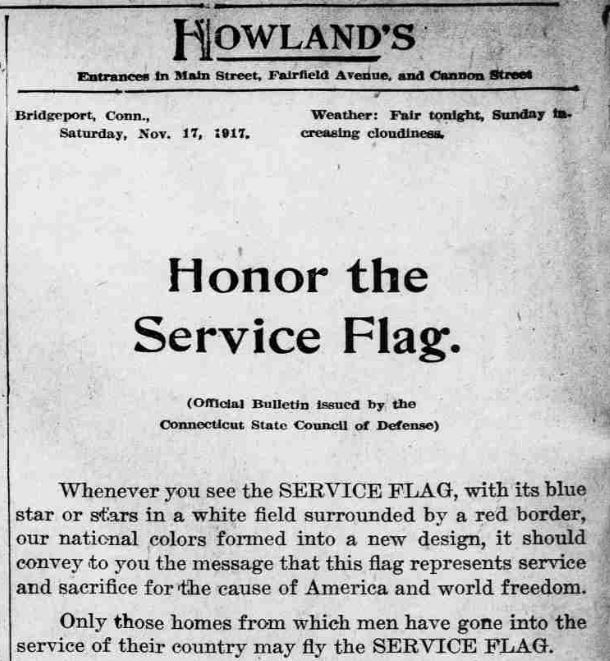

Advertisement for Howland’s, The Bridgeport Evening Farmer, Bridgeport, CT, November 17, 1917. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

“Have Service Flags for Norwich Women,” Norwich Bulletin, Norwich, CT, October 25, 1917. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Places to GO

- Most Connecticut towns have at least one war memorial, although they are sometimes “invisible,” even if in plain sight. Is there a monument to WWI veterans in your town? Visit at least one local WWI memorial and compare it to other town monuments, memorials, or historic markers. How is it similar to or different from other monuments, memorials, or markers? What information is conveyed? How does it make you feel? In what ways might your feelings have been different if you stood in front of this memorial in the years immediately following World War I? If your local World War I memorial isn’t already on the Connecticut World War One Memorials map, consider pinning it!

- Visit your local historical society or library to discover what original materials they have from WWI. You may find posters, photographs, letters, or personal accounts.

Things To DO

Check out additional primary sources related to this topic:

Poster – Join the Army Air Service, be an American eagle – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Poster – Gee!! I wish I were a man, I’d join the Navy – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Newspaper Article – “Military Strength of State Only 3,799 in National Guard and Naval Volunteers.” The Bridgeport Evening Farmer. (Bridgeport, CT), March 29, 1917 – Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Newspaper Article – “Practical Patriotism.” Norwich Bulletin. (Norwich, CT.), March 30, 1917. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Newspaper Article – “Marine Corps Ranks in Need of 4,000 Men.” The Bridgeport Evening Farmer. (Bridgeport, CT.), March 27, 1917. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

For more primary-source materials related to Word War I, visit the websites suggested below or search the Connecticut newspapers included in Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Websites to VISIT

Articles to READ

ConnecticutHistory.org:

- “Hartford’s Commemoration of World War I Servicemen and Women” by Christina Nhean.

- “World War I Flying Ace Raoul Lufbery” by David Drury.

CTExplored.org:

- “Restoring Connecticut’s Lost World War I Memorial” by Lynn Ferrari and Greg Secord. Connecticut Explored. Summer 2015, Volume 13, Number 3.

- “Join the Brave Throng” by Jessica Jenkins. Connecticut Explored. Winter 2014/15.

Smithsonian.com: “The Posters That Sold World War I to the American Public” by Jia-Rui Cook, Smithsonian, July 28, 2014.