Dr. Jason Chang and Karen Lau

University of Connecticut

TEACHER'S SNAPSHOT

Topics:

Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Studies, Foreign Policy, Maritime History, Slavery & Abolition, Work

Themes:

Cultural Diversity and an American National Identity, Globalization and Economic Interdependence, Role of Connecticut in U.S. History, Role of the United States in World Affairs, The Struggle for Freedom, Equality, and Social Justice

Town:

Mystic, New Haven, Stonington

Grade:

Grade 8

Historical Background

When the trade of enslaved Africans became illegal, many slave societies were already turning toward emancipation. In many parts of South America and the Caribbean, colonial plantation owners recreated the institution of forced labor through the importation of indentured workers from China and South Asia. These workers replaced the formerly enslaved Africans and were called “Coolies.” Today, it is a derogatory term that still circulates, more than a century and a half later. Ships from dozens of countries around the world participated in this brutal trade.

In 1852, a Connecticut businessman from New Haven named Lesley Bryson sailed his ship, the Robert Bowne, to China. He planned to deceive Chinese workers into believing they were headed to California. Instead, he planned to deliver them to the Guano Islands of Peru, where they would almost certainly die extracting fertilizer. This module explores Connecticut’s connection to this ghastly trade in human life by examining the voyage and mutiny aboard the Robert Bowne and exploring how the United States shaped the global trade in indentured Chinese workers during the 19th century.

D1: Potential Compelling Question

D1: POTENTIAL SUPPORTING QUESTIONS

- What was the Asian Coolie trade?

- In what ways was the Asian Coolie trade similar to and different from the trans-Atlantic slave trade?

- What are the connections between who shipped the Coolies and where they were sent?

- What was the role of Connecticut’s maritime industry in the Coolie trade?

D2: TOOL KIT

“The Massacre on the Robert Bowne.” Reprinted from the Hong Kong Register in The Times-Picayune. New Orleans. August 18, 1852, page 2. Courtesy of the Newspapers.com archive.

Note about the source: This article mentions that during the voyage, Captain Lesley Bryson and his crew cut the Chinese workers’ “tails.” This refers to the long, braided hair known as a “queue,” which was a mark of distinction and Chinese citizenship. Westerners called this hairstyle “tails” to deride Chinese laborers; forcibly cutting the hair was a great insult and a disgrace for the Chinese men.

Hound. Oil painting. © Mystic Seaport Museum, 1945.326.

Note about the source: The Hound was built in the Mallory shipyard in Mystic, Connecticut. It was owned by Captain Peck from Stonington, Connecticut. In July 1855, Peck arrived in Havana, Cuba with 230 Coolies, the maximum number allowed by U.S. law. Coolie labor was in such demand there that people protested against Captain Peck, saying he could have transported 400 Coolies on the ship under Spanish law.

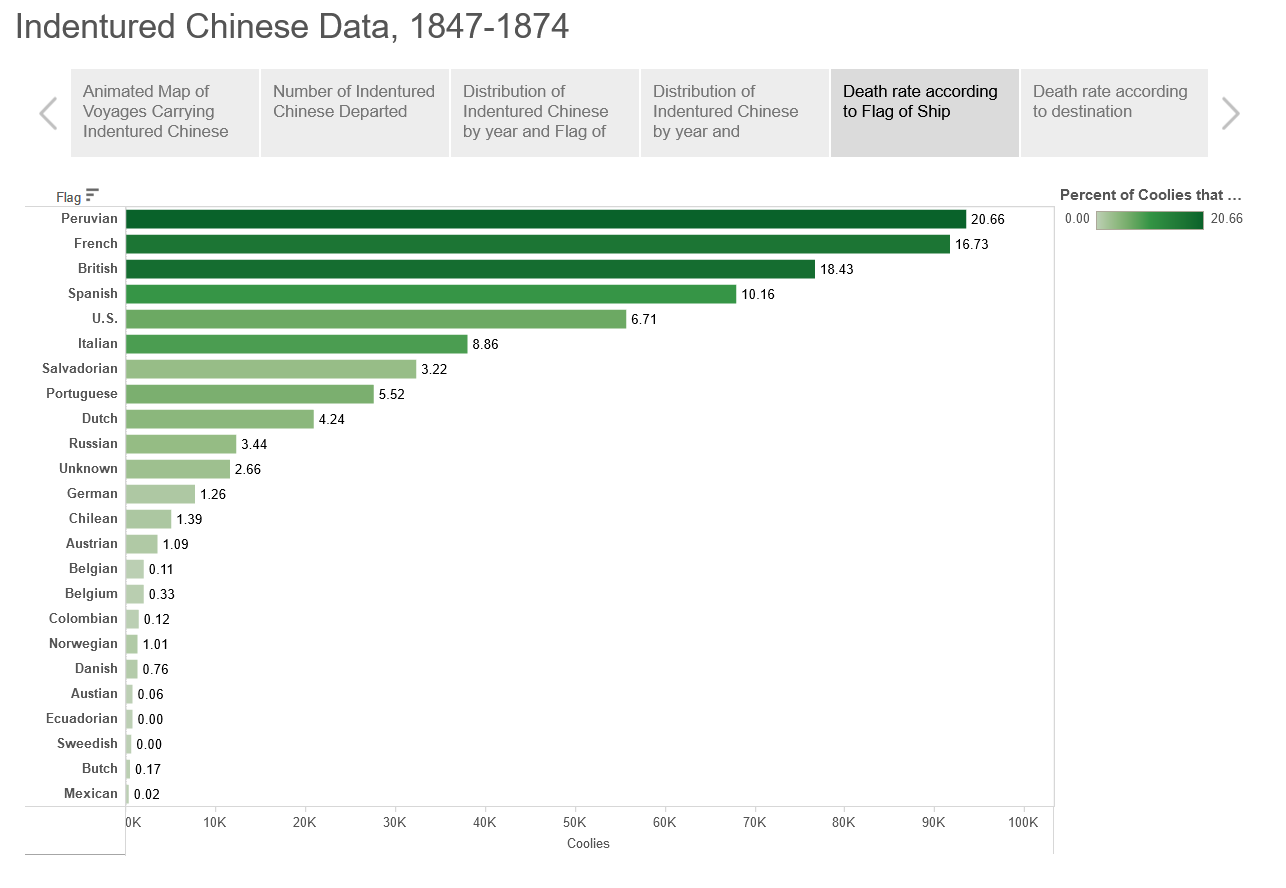

Coolie Voyages by Jason Chang. Visualizations of Indentured Chinese Data, 1847-1874.

Note about the source: The data used in this Tableau Public visualization come from The Coolie Trade: The Traffic in Chinese Laborers to Latin America. Arnold Meagher. Xlibris Corporation, 2008. This data supports inquiry about the international composition of the fleet, the volume of trade by destination, the geographic distribution of indentured Chinese workers, and the mortality rate aboard Coolie vessels. President Abraham Lincoln banned the Coolie trade in 1862.

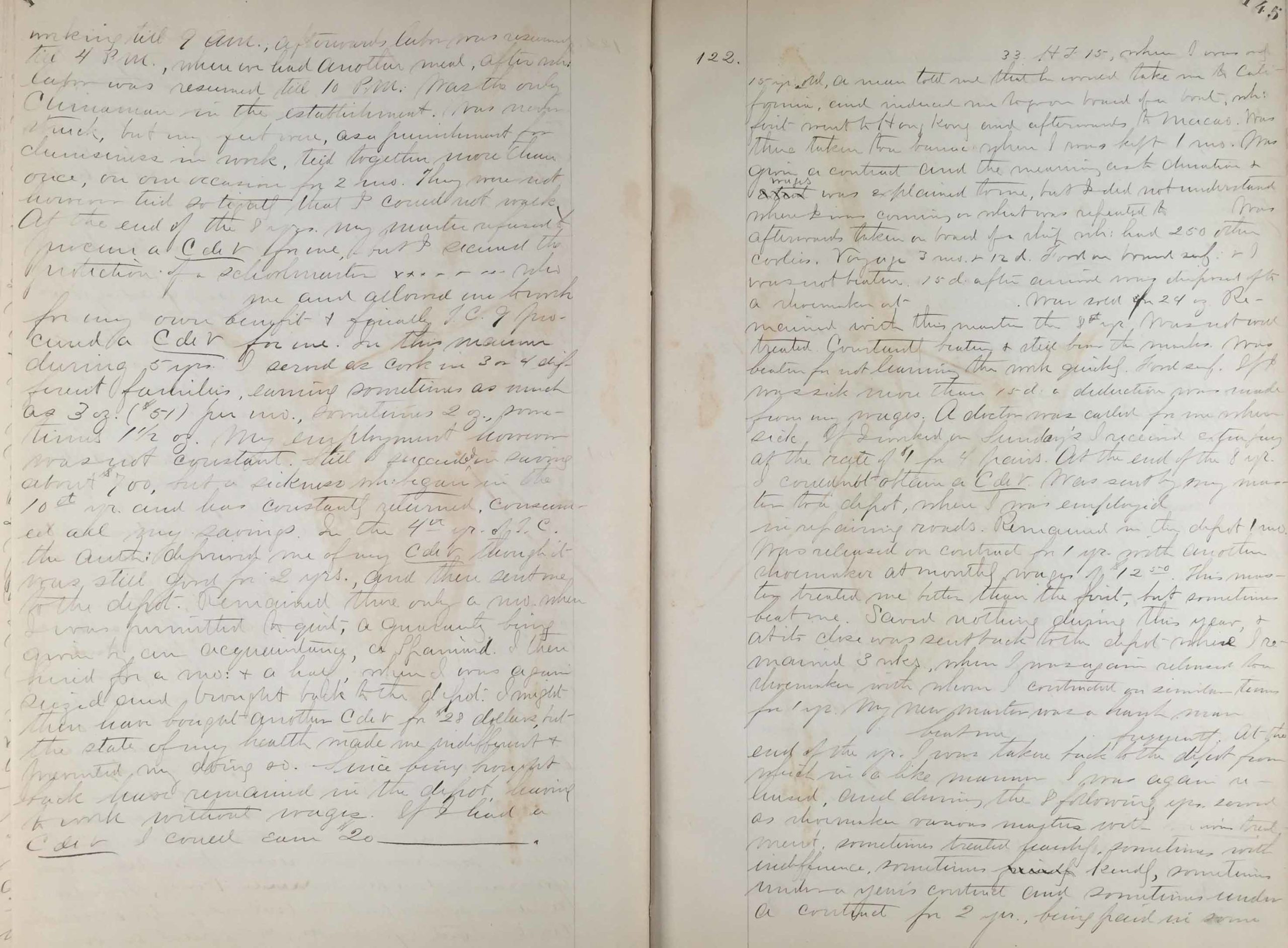

Journal with testimonies from Chinese survivors of the Coolie era, author unknown, 1913-1914. Connecticut State Library. Sample manuscript page and transcription of four entries.

Note about the source: The statements included in this journal detail the harsh experiences of indentured workers in Havana, Cuba. Interviewees describe the contracts they signed that were later violated and the mistreatment they suffered aboard ships. They include vivid details about deaths and beatings they witnessed. They describe conversations between soldiers and laborers, poor interactions with doctors, and their longing to return home and see their family. The journal might have been kept by one of Yung Wing’s protégés. Yung Wing served on the 1874 Cuba Commission, which helped dismantle the Coolie trade.

“The Coolie Trade.” The Inquirer and Connecticut Mirror. September 24, 1856, page 2. Courtesy of the Newspapers.com archive.

D3: INQUIRY ACTIVITY

- Individually or as a class, students will read the article, “The Massacre on the Robert Bowne.” Using the Library of Congress Primary Source Analysis Tool worksheet, the SOAPSTone technique, or any other analysis tool of your choice, students will record the information they discover from the article, their thoughts (or what assumptions they can make), and their questions.

- In pairs or small groups, students will examine the painting, journal excerpt, newspaper articles, and online data visualization in order to gather additional information about the Coolie trade. Encourage them to dig into the WHO, WHAT, WHEN, WHERE, HOW, and WHY of this aspect of Connecticut, American, and world history. Students will share their findings in a class discussion.

- After these inquiries into the sources, engage in a class discussion about what new questions students have. Revisit the compelling question, and notice how the introduction of the Coolie history disrupts simplistic narratives about race, slavery, and emancipation during the mid-19th century.

D4: COMMUNICATING CONCLUSIONS

- Using data from Tableau Public, students will create infographics to depict the number of Coolies departing China, the number of Coolie deaths aboard ships, and the number of Coolies working at plantations in different countries.

- To build insight and empathy, students will examine the image of the Hound and read the Coolie testimonies. In pairs, students will write a fictional correspondence between the Chinese worker in Cuba and a family member in China. What would they say? How would they explain how they ended up in Cuba? How would they describe their voyage? How would they describe life in Cuba?

- Students will create a Venn diagram to compare the similarities and differences between the mutiny aboard Robert Bowne and La Amistad. (For a classroom activity related to the Amistad, see The Amistad Incident and the Face of Slavery.)

- Students will create a timeline of the Coolie trade and the Civil War and discover correlations between the two events.

- Students will write an essay or create a presentation comparing the 1862 U.S. ban on participation in the Coolie trade and the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Place to GO

Custom House Maritime Museum, New London, which holds materials about Connecticut’s participation in the “China Trade” (1783-1844). Materials about the Amistad are also available. School programs available.

Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, which has both permanent and changing exhibits and interpretive programs about American maritime history, including the local shipbuilding industry. The reproduction of the Amistad was also built at the museum’s shipyard. School programs available.

Things To DO

Encourage students to explore the history of the 1852 Robert Bowne Rebellion by reading the new graphic novel The Cargo Rebellion: Those Who Chose Freedom, written by Jason Chang, Ben Barson, and Alexis Dudden and Illustrated by Kim Inthavong. PM Press, 2023. Available for pre-order from PM Press.

Watch Coolies: How the British Reinvented Slavery, a BBC documentary about the history of the Coolie trade from the vantage point of the South Asian indentured experience.

Watch Ancestors in the Americas from PBS by Asian American director Loni Ding. Videos available to patrons of selected public libraries with their card number on Kanopy.

Read the Act to prohibit the ‘coolie trade’ (1862)

Read The Making of Asian America by Erika Lee. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Read The Cuba Commission Report: A Hidden History of the Chinese in Cuba. The Original English-Language Text of 1876. Introduction by Denise Helly. Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Websites to VISIT

Coolie Voyages on Tableau Public

Articles to READ

“A History Of Indentured Labor Gives ‘Coolie’ Its Sting” by Lakshmi Gandhi, NPR Code Switch, November 25, 2013.

“The Voyage of the ‘Coolie’ Ship Kate Hooper, October 3, 1857–March 26, 1858” by Robert J. Plowman. Prologue Magazine, Summer 2001, Vol. 33, No. 2.

“Investigation of the Coolie Traffic in Peru.” Chapter XVIII of My Life in China and America by Yung Wing. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1909.