by Rebecca Furer for Teach It

TEACHER'S SNAPSHOT

Subjects:

African Americans, Individuals in History, Slavery & Abolition, Women

Course Topics/Big Ideas:

The Struggle for Freedom, Equality, and Social Justice

Town:

Farmington, New Haven, New London, Statewide

Grade:

Grade 8

Lesson Plan Notes

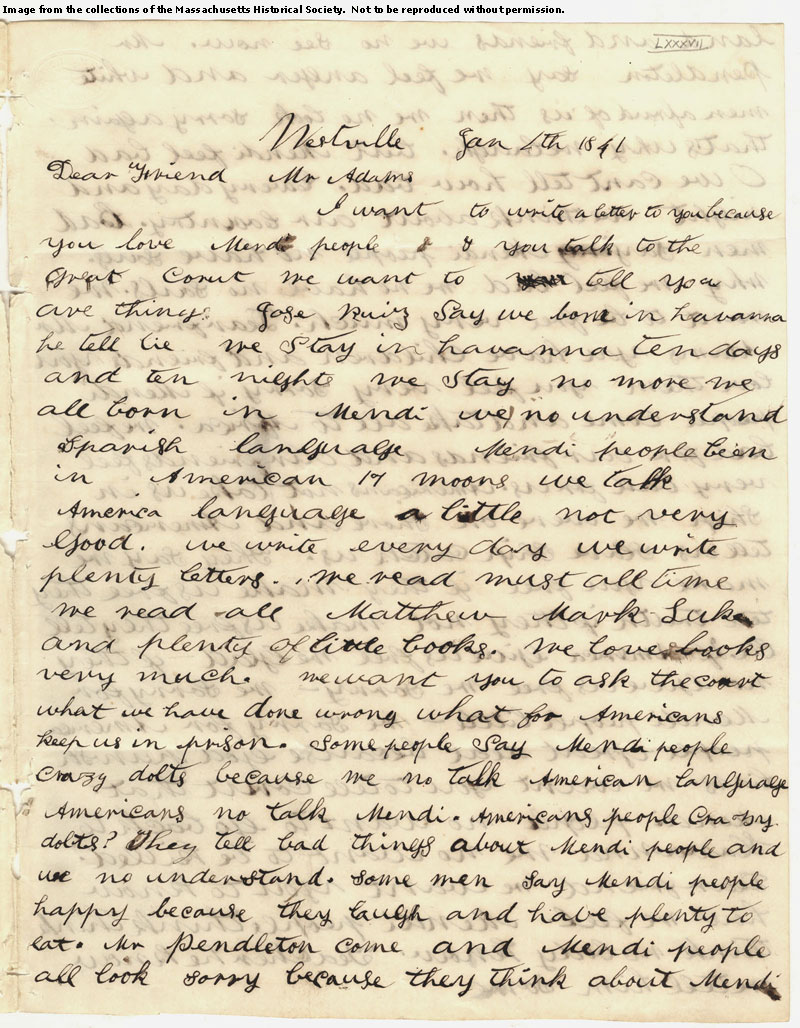

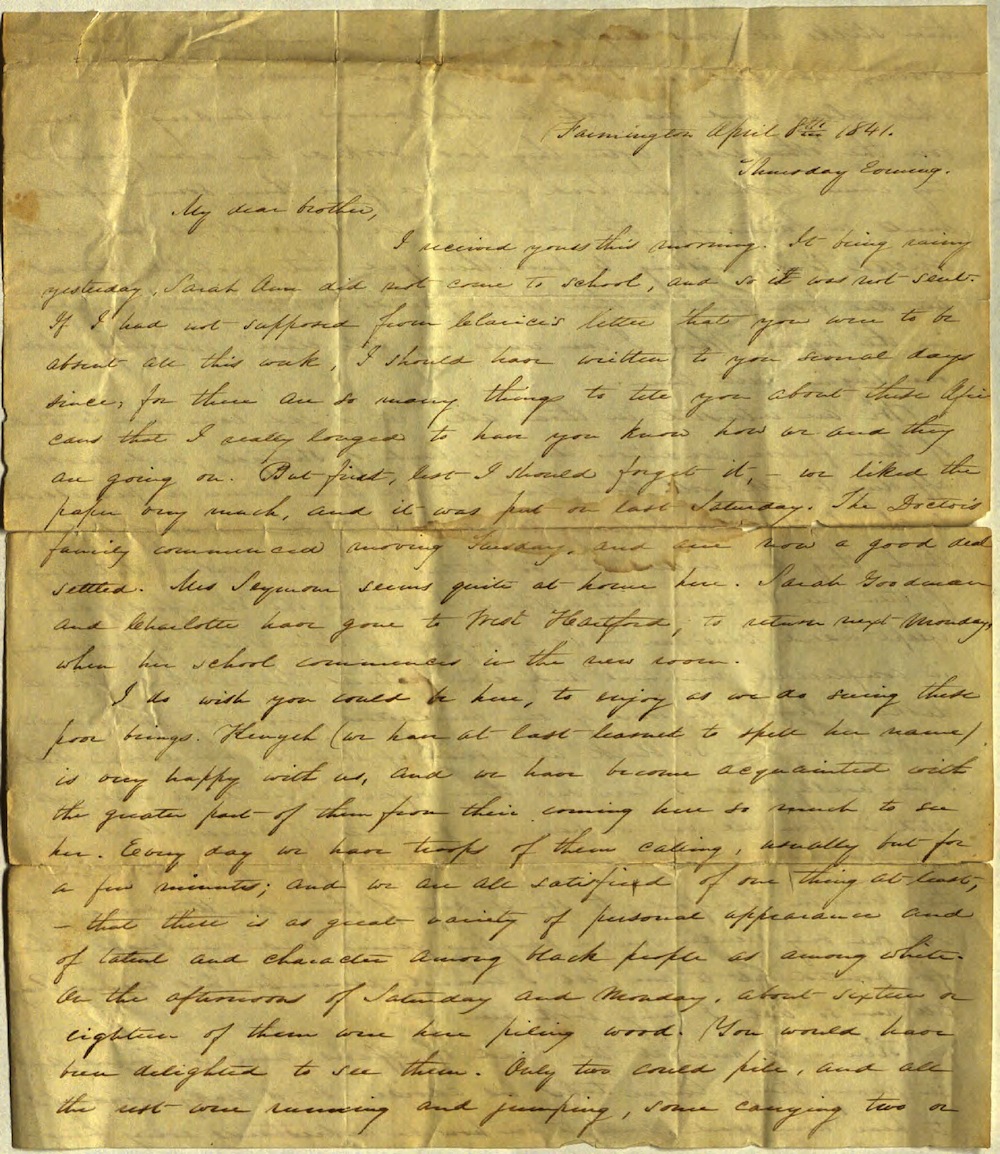

Most people in Connecticut in 1839 probably understood very little about Africa or Africans when the schooner La Amistad was brought into New London Harbor with dozens of Africans—Mende men, boys, and girls—on board. Even among those residents who supported the abolitionist cause, few had ever met a person born in Africa. Locals came to the prison in Westville (New Haven) and paid to gawk at the captives, who were awaiting trial. While in Westville, eleven-year-old Kale—one of the youngest of the Mende captives—studied English. Kale wrote to John Quincy Adams, who was to defend the Amistad Africans before the Supreme Court. Following the trial, the Mende lived with families in Farmington for eight months as they sought funds to return home to Africa. The Cowles family supported the abolitionist movement and hosted one of the little girls from the Amistad. The letters written by Charlotte Cowles (who was about twenty-one at the time) to her brother Samuel reveal both her preconceived ideas and growing understanding of the Mende living in her community.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

SUPPORTING QUESTIONS

- What kinds of personal interactions did the Amistad Africans and Connecticut residents have?

- In what ways did the Amistad incident help people in Connecticut—and in the United States—view enslaved Africans as “real people”?

- How did these two young writers use language to elicit particular emotions about the Mende and their situation?

ACTIVITY

Divide the class into pairs or groups and assign each group one of the three letters from the toolkit. The original letters are best viewed online. The transcriptions can be downloaded and printed.

Note that because of the length of the Charlotte Cowles letters, certain less-pertinent sections have been “greyed-out.” Students need not focus on those portions in their analysis.

Using SOAPSTone analysis, the Library of Congress Analyzing Primary Sources process, or another method of your choice, have students investigate their assigned source.

- What can students KNOW from the source? What is the evidence?

- What can they GUESS or infer? Based on what?

- What does the source make them WONDER?

Students can then piece together their findings or rotate sources until each group has investigated each source.

Revisit the supporting and compelling question, as well as the questions students have developed and shared. Improve/fine-tune the new questions and discuss what other sources might exist to help answer these questions.

Once students have examined the letters, you may want to share portraits of some of the Mende people mentioned. Links to William H. Townsend’s drawings, John Warner Barber’s silhouettes and biographical sketches, and Nathaniel Jocelyn’s portrait of Cinque/Sengbe Pieh referenced by Charlotte Cowles can be found below in the “Additional Resources” section.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR ASSESSMENT

The Mende stayed in Farmington for months while they and their supporters worked to raise money to help them return to Africa. Writing from the perspective of Charlotte Cowles or one of the Mende children, students will write a letter to the editor of the Charter Oak, an abolitionist newspaper in Connecticut at the time, to convince the newspaper’s readers to contribute money to the cause.

RESOURCE TOOL KIT

Things you will need to teach this lesson:

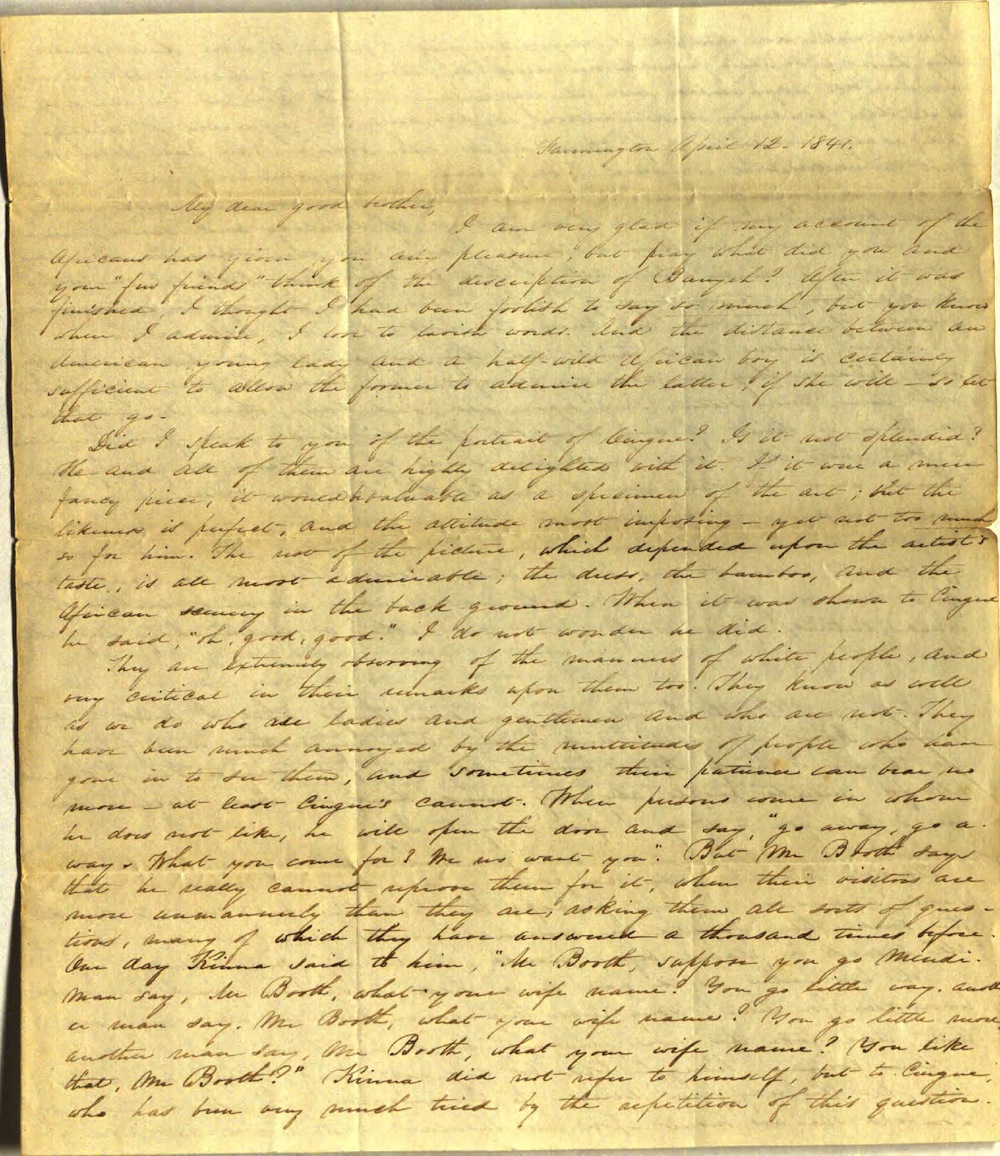

Letter from Kale to John Quincy Adams, January 4, 1841. Written from Westville (New Haven), CT – Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

You can link to a complete transcription here or download the transcription as a PDF.

Letter from Charlotte to Samuel Cowles, April 8, 1841. Written from Farmington, CT – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History.

Transcription of this letter as a PDF.

Letter from Charlotte to Samuel Cowles, April 12, 1841. Written from Farmington, CT – Connecticut Museum of Culture and History.

Transcription of this letter as a PDF.

Library of Congress Primary Source Analysis Tool Worksheet

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Places to GO

Farmington Historical Society | Farmington Freedom Trail: Tours available seasonally.

Connecticut Museum of Culture and History: School programs available.

New Haven Museum: School programs available.

Things To DO

Examine more primary sources from the Amistad case:

Sketches of the Amistad captives made by William H. Townsend, ca. 1839-40. Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library – Drawings of the Amistad Prisoners, New Haven

Library of Congress, American Memory, Lewis Tappan Papers – Affidavit of Kimbo, an Amistad African, Affidavit of Singweh, an Amistad African

National Archives at Boston – Trial of the Century: La Amistad – Warrant for Habeas Corpus, United States v. Cinque and the Africans

The portrait of Cinque/Sengbe Pieh by Nathaniel Jocelyn, made in 1840 and referenced in Charlotte Cowles’ letter. Original painting in the collection of the New Haven Museum.

Websites to VISIT

Mystic Seaport for Educators: Amistad Resource Set

National Park Service: The Amistad Story

National Archives: Teaching with Documents – The Amistad Case

Library of Congress online exhibition: The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship

The Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale: The Amistad Case

Articles to READ

ConnecticutHistory.org: