endawnis Spears

Akomawt Educational Initiative

TEACHER'S SNAPSHOT

Topics:

Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Studies, Belief & Religion, Education, Individuals in History, Native/Indigenous Peoples

Town:

Cornwall, Lebanon, Plainfield

Grade:

Grade 8

Historical Background

As a result of The Second Great Awakening (the protestant religious revival in the United States, 1795-1835), several schools that focused on the conversion and assimilation of Native children from near and far were established in Connecticut, including the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Moor’s Indian Charity School in Lebanon, and Plainfield Academy in Plainfield. This approach to assimilation later became systematized in the U.S. government-backed boarding school era (1860-1978), which used forcible extraction of Indigenous children.

The boarding schools in Connecticut did not take Native children from their communities via outright coercion; many children were voluntarily sent to these schools by their families in the hopes that educating them in white schools would yield leaders that would be beneficial for their home communities. Many of these Indigenous students went on to lead notable lives; others died while attending school far away from home.

Several students are highlighted in this activity. Find more information about the students in the Toolkit section below.

D1: Potential Compelling Question

D1: POTENTIAL SUPPORTING QUESTIONS

- Who has the power to create primary sources?

- What do students say in their letters, and what is left unsaid?

- What was the stated purpose of the mission schools?

D2: TOOL KIT

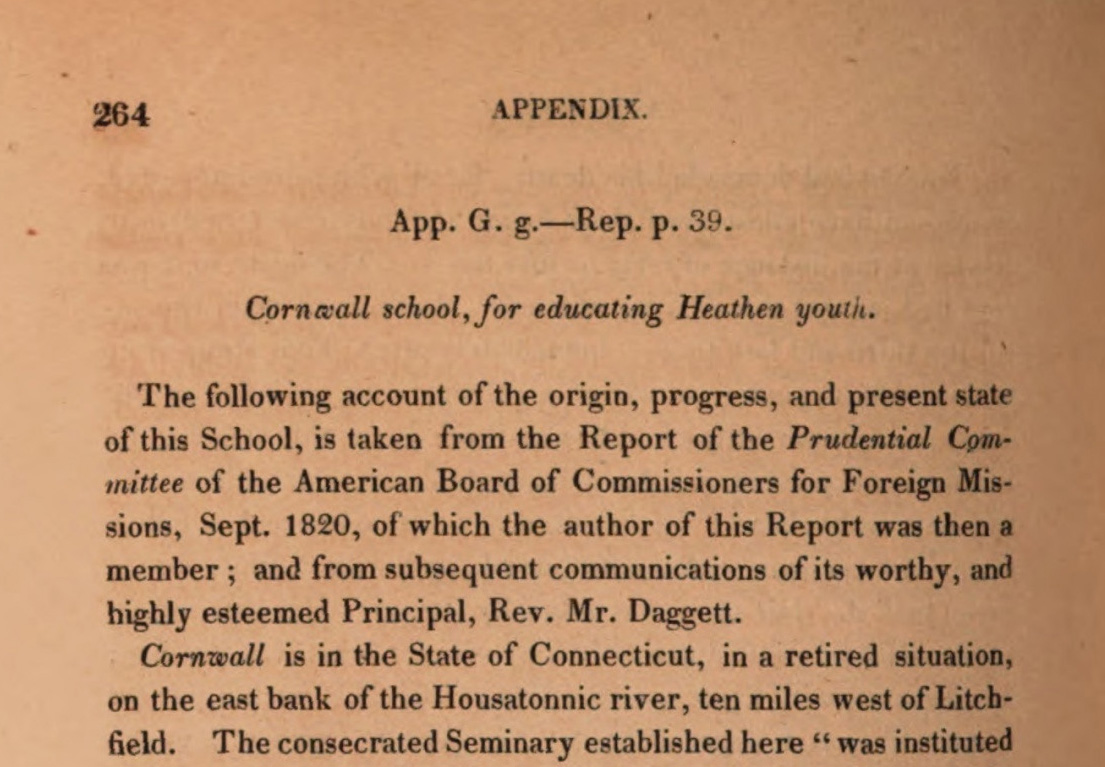

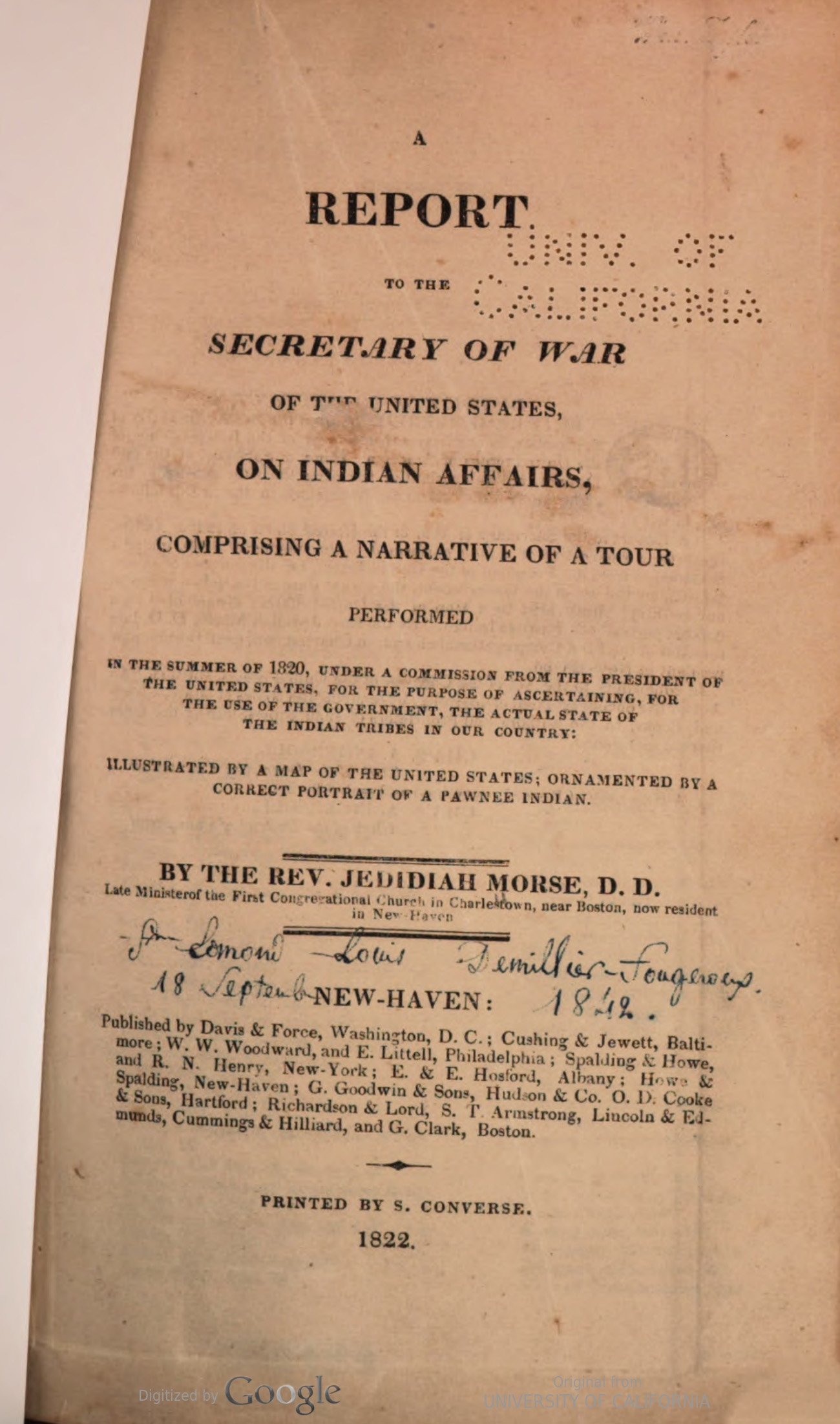

Introduction to the Appendix about the Cornwall Foreign Mission from A report to the secretary of war of the United States, on Indian affairs, comprising a narrative of a tour performed in the summer of 1820, under a commission from the President of the United States… by the Rev. Jedidiah Morse. New-Haven: Printed by S. Converse, 1822, pages 264-265.

University of California, courtesy HathiTrust

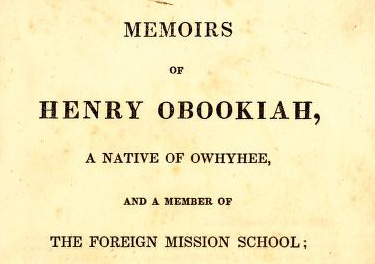

Excerpt from Memoirs of Henry Obookiah, a native of Owhyhee, and a member of the Foreign Mission School by Dwight, E. W. Philadelphia: American Sunday School Union, 1830, pages 33-35, 43.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, courtesy Internet Archive.

Henry Opukaha’ia was a Native Hawaiian student from what at the time was referred to as the Sandwich Islands. Henry had a traumatic childhood and seized the opportunity to sail to “New England” at the age of 16 in 1808. The excerpt from the memoirs of Henry Opukaha’ia tells us a bit about his plans for once he is done with school.

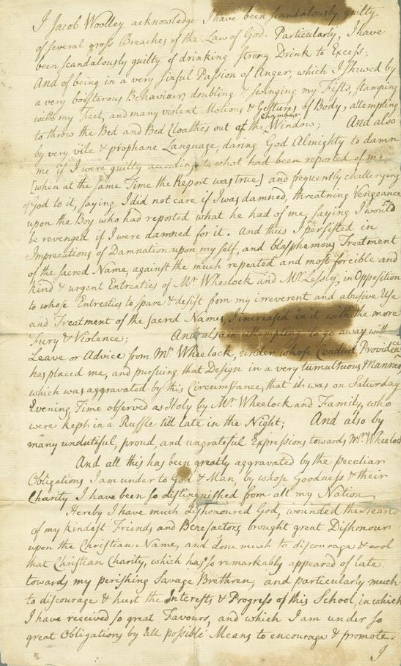

Excerpts of letters from Moor’s Indian Charity School Collection, Dartmouth College.

Jacob Woolley, confession, 1763 July 25, ms-number: 763425.2.

Daniel Simon, letter, to Eleazar Wheelock, 1771 September, ms-number: 771540.

Jacob Woolley was a Lenape (Delaware) student at Moor’s Indian Charity School beginning in 1754. He was one of the first Native students to study under the school’s founder, Eleazar Wheelock. The “confession” from Jacob Woolley sheds light on how teenage behavior was characterized in the mission schools.

Daniel Simon was a Narragansett student who attended Moor’s Indian Charity School with his brother Abraham beginning in either 1768 or 1769. The letter from Daniel Simon is one of the most honest accounts from a Native student regarding their feelings about their educational experience at one of the schools.

While the transcripts of the full letters are provided, students can focus on the yellow highlighted sections.

Excerpts of student and parent letters from A report to the secretary of war of the United States, on Indian affairs, comprising a narrative of a tour performed in the summer of 1820, under a commission from the President of the United States… by the Rev. Jedidiah Morse. New-Haven: Printed by S. Converse, 1822, pages 267-268, 272, 275-276.

University of California, courtesy HathiTrust

The letters published in the report to the Secretary of War (before the Department of Interior, the Department of War oversaw “Indian” affairs) were used to justify potential funding.

John Ridge was the son of prominent Cherokee political leader, Major Ridge. He lived in Cherokee homelands, or Georgia, prior to forced removal to Indian Territory. He began attending the Foreign Mission School in 1819 and was later joined by his cousin, Elias Boudinot. Ridge and Boudinot were threatened and harassed when they began romantic relationships with white women in Cornwall.

The letter from Elias Boudinot shows how correspondence with benefactors speaks to the purpose and goals of the mission schools. A short letter from his mother is also included.

John Ridge’s letter uses terms that would appeal to the reader, e.g. referencing the need to move toward civilization, the importance of being educated “like the whites.”

While the full letters are provided, students can focus on the red underlined sections.

D3: INQUIRY ACTIVITY

1. Introduce and discuss the compelling question. What are examples of primary sources? How do we learn about the past?

2. Share the introduction to the Appendix about the Cornwall Foreign Mission School from the Report to the Secretary of War, 1822, and read through it together as a class. What was the stated purpose of the school (from the school’s constitution)? What other information does the introduction provide?

3. Explain that there were several schools in Connecticut that had Indigenous students from both near (tribes from Connecticut, New York, and Rhode Island) and far, including Henry Opukaha’ia, who was Native Hawaiian from Hawaii, and John Ridge, who was Cherokee from Georgia. The schools were: the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall (1817-1826), Moor’s Indian Charity School in Lebanon (1754- 1850), and Plainfield Academy in Plainfield (1770-1890).

4. Break students into three groups and assign one set of sources to each. Ask the students to read their assigned sources as a group and discuss:

- When was each source created?

- Who was the author of each source, and who do you think the audience was?

- In your own words, what does the author say?

- What do you infer or read between the lines?

- What questions does your group have about this source?

- If you were friends of these students from home, what questions would you ask them about their experiences?

5. Have each group report back to the class about their resources. Discuss as a class both what the Indigenous students said and what seems to be left unsaid.

6. Revisit the compelling and supporting questions. Because most of the primary sources from Indigenous students attending these schools at the time were used to generate continued funding for the schools, they can lack information about how the students truly experienced their education. Many Native people today are reflecting on the experiences of their ancestors through scholarship, art, and activism. Some examples are included below.

D4: COMMUNICATING CONCLUSIONS

- Imagine you are a friend from home (Cherokee Nation, Georgia) and write a letter to John Ridge while he is attending school in Cornwall, Connecticut. What questions would you ask him about his school experience? What would you want to know more about? Are there things you can share about what was going on in your own community at the time? Reflect on how you might be feeling or how John Ridge might have felt.

- Read this article in the Hartford Courant about Henry Opukaha’ia’s repatriation to Hawaii: “A Final Resting Place for Henry Opukahala.” Then watch this video about a Native Hawaiian organization repatriating Hawaiian relatives: “Ka Ho’ina: Going Home” (21:05). Write a report or create a presentation about the repatriation of Native relatives to their homelands. Be sure to define the term “repatriation.” Answer the questions: What is repatriation? Why is it important? Why were Hawai’ian bodies being held in museums? How is repatriation part of Henry Opukaha’ia’s story?

- Watch the video of this play: “My Name Is Opukaha’ia,” written and performed by Moses Goods (Native Hawai’ian), presented by the American Antiquarian Society, 2019. (27:32). Imagine that you are a theater critic for a newspaper and you are writing a review about the play. What is the story being told? What are the parts of the play that were the most impactful to you? Why? This play only covers a short period of Henry’s life. What other parts of his life would you like to see a play written and performed about?

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Place to GO

Cornwall Historical Society, Cornwall

Henry Opukaha’ia’s former grave site, Cornwall

Things To DO

Cornwall Historical Society Foreign Mission School Virtual Tour

Listen to this episode of the podcast “This Land” (34:08)

Watch Cherokee Leader Major Ridge and the Indian Removal Act (5:25)

Read a book to learn more:

- The Long Journeys Home: The Repatriations of Henry ‘Opukaha‘ia and Albert Afraid of Hawk by Nick Bellantoni

- Memoirs of Henry Obookiah

- The Heathen School by John Demos

Websites to VISIT

Dartmouth College: Collections from Moor’s Indian Charity School

University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections: Portrait of John Ridge (Cherokee) ca 1771-1836 and accompanying biography

National Museum of the American Indian: The Trail of Tears: A Story of Cherokee Removal

Connecticut State Department of Education: Teaching Native American Studies

Articles to READ

“What’s in a name? A note on terminology” by the Turtle Island Social Studies Collective

“Memoirs of Henry Obookiah: A Rhetorical History.” The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 38 (2004)

“Through Our Own Eyes: A Chickasaw Perspective on Removal”

“Young Love at Cornwall’s Foreign Mission School” by Zachary Keith and Katherine Hermes. Connecticut Explored, Winter 2016-2017.

Connecticut History.org: “An Experiment in Evangelization: Cornwall’s Foreign Mission School”